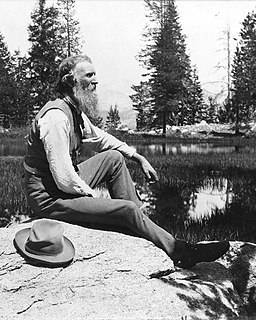

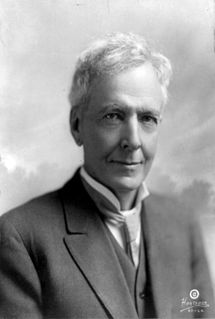

Top 212 Quotes & Sayings by Aldo Leopold - Page 2

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American environmentalist Aldo Leopold.

Last updated on December 25, 2024.

I am asserting that those who love the wilderness should not be wholly deprived of it, that while the reduction of the wilderness has been a good thing, its extermination would be a very bad one, and that the conservation of wilderness is the most urgent and difficult of all the tasks that confront us, because there are no economic laws to help and many to hinder its accomplishment.

In that year [1865] John Muir offered to buy from his brother ... a sanctuary for the wildflowers that had gladdened his youth. His brother declined to part with the land, but he could not suppress the idea: 1865 still stands in Wisconsin history as the birth-year of mercy for things natural, wild, and free.

The government tells us we need flood control and comes to straighten the creek in our pasture. The engineer on the job tells us the creek is now able to carry off more flood water, but in the process we have lost our old willows where the owl hooted on a winter night and under which the cows switched flies in the noon shade. We lost the little marshy spot where our fringed gentians bloomed.

Acts of creation are ordinarily reserved for gods and poets, but humbler folk may circumvent this restriction if they know how. To plant a pine, for example, one need be neither god nor poet; one need only own a shovel. By virtue of this curious loophole in the rules, any clodhopper may say: Let there be a tree - and there will be one.

Then came the gadgeteer, otherwise known as the sporting-goods dealer. He has draped the American outdoorsman with an infinity of contraptions, all offered as aids to self-reliance, hardihood, woodcraft, or marksmanship, but too often functioning as substitutes for them. Gadgets fill the pockets, they dangle from neck and belt. The overflow fills the auto-trunk and also the trailer. Each item of outdoor equipment grows lighter and often better, but the aggregate poundage becomes tonnage.

Ideas, like men, can become dictators. We Americans have so far escaped regimentation by our rulers, but have we escaped regimentation by our own ideas? I doubt if there exists today a more complete regimentation of the human mind than that accomplished by our self-imposed doctrine of ruthless utilitarianism.

Conservation is getting nowhere because it is incompatible with our Abrahamic concept of land. We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect. There is no other way for land to survive the impact of mechanized man, nor for us to reap from it the aesthetic harvest it is capable, under science, of contributing to culture

For unnumbered centuries of human history the wilderness has given way. The priority of industry has become dogma. Are we as yet sufficiently enlightened to realize that we must now challenge that dogma, or do without our wilderness? Do we realize that industry, which has been our good servant, might make a poor master?

We realize the indivisibility of the earth - its soil, mountains, rivers, forests, climate, plants, and animals - and respect it collectively not only as a useful servant but as a living being, vastly less alive than ourselves in degree, but vastly greater than ourselves in time and space - a being that was old when the morning stars sang together, and when the last of us has been gathered unto his fathers, will still be young.

We all strive for safety, prosperity, comfort, long life, and dullness. The deer strives with his supple legs, the cowman with trap and poison, the statesman with pen, the most of us with machines, votes, and dollars. A measure of success in this is all well enough, and perhaps is a requisite to objective thinking, but too much safety seems to yield only danger in the long run. Perhaps this is behind Thoreau's dictum: In wilderness is the salvation of the world. Perhaps this is the hidden meaning in the howl of the wolf, long known among mountains, but seldom perceived among men.

Wilderness is a resource which can shrink but not grow. Invasions can be arrested or modified in a manner to keep an area usable either for recreation, science or for wildlife, but the creation of new wilderness in the full sense of the word is impossible. It follows, then, that any wilderness program is a rearguard action, through which retreats are reduced to a minimum.

Our children are our signature to the roster of history; our land is merely the place our money was made. There is as yet no social stigma in the possession of a gullied farm, a wrecked forest, or a polluted stream, provided the dividends suffice to send the youngsters to college. Whatever ails the land, the government will fix it.

Wilderness is the raw material out of which man has hammered the artifact called civilization. Wilderness was never a homogenous raw material. It was very diverse. The differences in the product are known as cultures. The rich diversity of the worlds cultures reflects a corresponding diversity. In the wilds that gave them birth.

One of the anomalies of modern ecology is the creation of two groups, each of which seems barely aware of the existence of the other. The one studies the human community, almost as if it were a separate entity, and calls its findings sociology, economics and history. The other studies the plant and animal community and comfortably relegates the hodge-podge of politics to the liberal arts. The inevitable fusion of these two lines of thought will, perhaps, constitute the outstanding advance of this century.