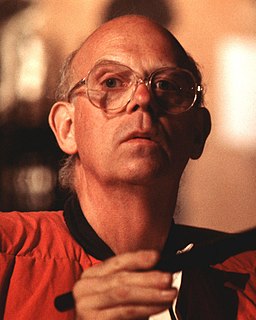

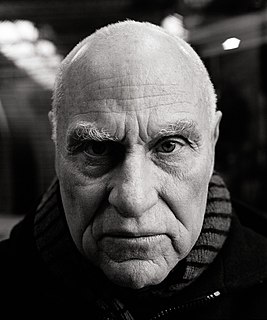

Top 62 Quotes & Sayings by Claes Oldenburg

Explore popular quotes and sayings by a Swedish sculptor Claes Oldenburg.

Last updated on April 20, 2025.

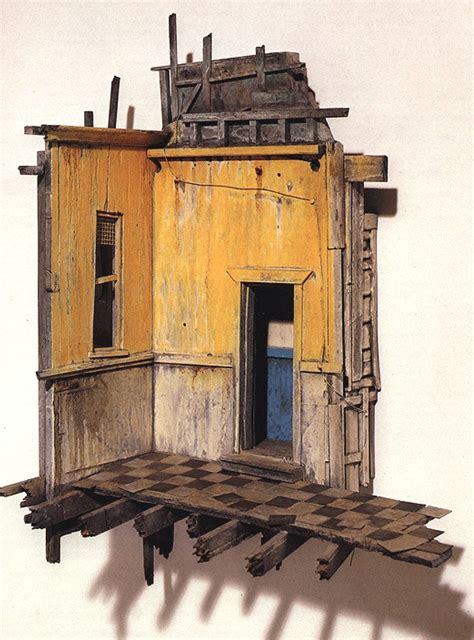

I was always interested in drawing. As a child, I started my own country, which was called Neubern. It was located in the South Atlantic. I did the documentation of Neubern in great detail. I drew everything that was there, all the houses and all the cars and all the people. We even had a navy and an air force. I spent a lot of time drawing.

I am preoccupied with the possibility of creating art which functions in a public situation without compromising its private character of being antiheroic, antimonumental, antiabstract, and antigeneral. The paradox is intensified by the use on a grand scale of small-scale subjects known from intimate situations--an approach which tends in turn to reduce the scale of the real landscape to imaginary dimensions.