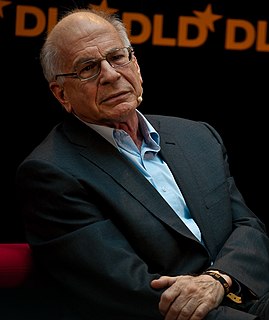

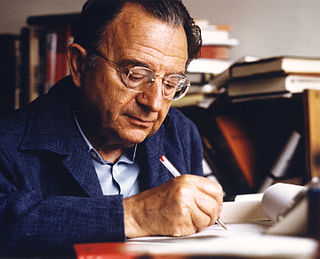

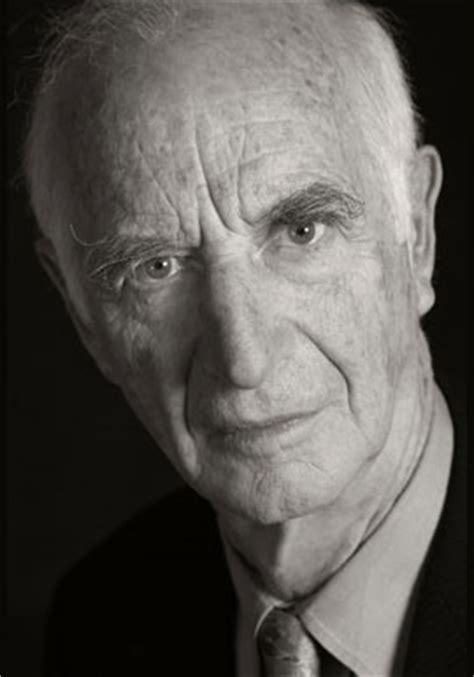

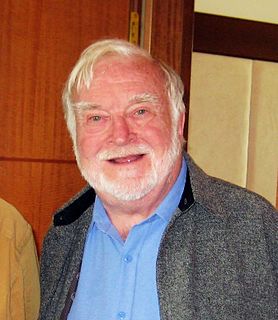

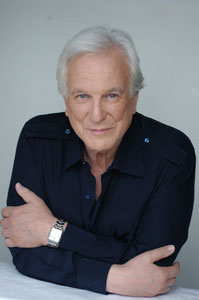

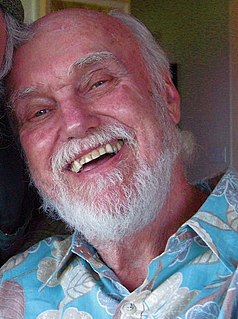

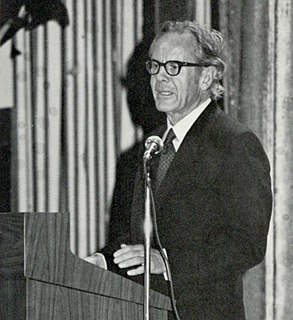

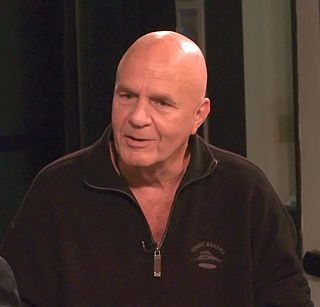

Top 223 Quotes & Sayings by Daniel Kahneman

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an Israeli psychologist Daniel Kahneman.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

Doubting what you see is a very odd experience. And doubting what you remember is a little less odd than doubting what you see. But it's also a pretty odd experience, because some memories come with a very compelling sense of truth about them, and that happens to be the case even for memories that are not true.

Suppose you like someone very much. Then, by a familiar halo effect, you will also be prone to believe many good things about that person - you will be biased in their favor. Most of us like ourselves very much, and that suffices to explain self-assessments that are biased in a particular direction.