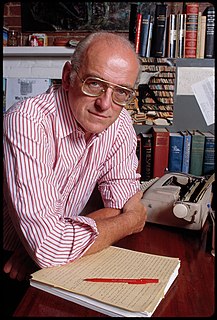

Top 72 Quotes & Sayings by Donald E. Westlake

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American writer Donald E. Westlake.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

There are a couple of writers I admired who were very good at giving the character's emotion without stating what that emotion was. Not saying "He was feeling tense," instead saying, "His hand squeezed harder on the chair arm," as if staying outside the guy. I wanted to try doing that. I wanted to have a really emotional story in which the characters' emotions are never straight - out told to you, but you get it.

Parker wasn't supposed to be a series. He was supposed to be one book, and if he was only going to be in one book, I didn't worry about it. And then an editor at Pocket Books said "Write more books about him." So I didn't go back at that point and give him a first name. If I'd known he would've been a series, I would've done two things differently. First, I would've given him a first name because that means for 27 books, I've had to find some other way to say, "Parker parked the car."

I don't think I would have been a good architect. Really, I have thought about this from time to time, and I might have wound up like my father, who never did find that which he could devote his life to. He sort of drifted from job to job. He was a traveling salesman, he was a bookkeeper, he was an office manager, he was here, there, there. And however enthusiastic he was at the beginning, his job would bore him. If I hadn't had the writing, I think I might have replicated what he was doing, which would not have been good.

If your subject is crime, then you know at least that you're going to have a real story. If your subject is the maturing of a college boy, you may never stumble across a story while you're telling that. But if your story is a college boy dead in his dorm room, you know there's a story in there, someplace.

I was writing everything. I grew up in Albany, New York, and I was never any farther west than Syracuse, and I wrote Westerns. I wrote tiny little slices of life, sent them off to The Sewanee Review, and they always sent them back. For the first 10 years I was published, I'd say, "I'm a writer disguised as a mystery writer." But then I look back, and well, maybe I'm a mystery writer. You tend to go where you're liked, so when the mysteries were being published, I did more of them.

Years ago, I heard an interview with violinist Yehudi Menuhin. The interviewer said, "Do you still practice?" And he said, "I practice every day." He said, "If I skip a day, I can hear it. If I skip two days, the conductor can hear it. And if I skip three days, the audience can hear it." Oh, yes, you have to keep that muscle firm.

The other thing that I got back then - the Parker novels have never had much of anything to do with race. There have been a few black characters here and there, but the first batch of books back then, I got a lot of letters from urban black guys in their 20s, 30s, 40s. What were they seeing that they were reacting to? And I think I finally figured it out - at that time, they were guys who felt very excluded from society, that they had been rejected by the greater American world.

I'm one of the narrative-push people. I don't outline, I don't plan ahead. So I'm my first reader, telling myself the story as I'm going along. Since I haven't designed it ahead of time, each day I have to be sure that the footing is solid before I make the next step. I think you could be more intricate if you work it out ahead of time.

I know people who have suffered writer's block, and I don't think I've ever had it. A friend of mine, for three years he couldn't write. And he said that he thought of stories and he knew the stories, could see the stories completely, but he could never find the door. Somehow that first sentence was never there. And without the door, he couldn't do the story. I've never experienced that. But it's a chilling thought.

I've had stuff of mine adapted by other people, so I've come to the conclusion that a movie is a different form from a novel and there is no such thing as a true adaptation. You have to adapt to this other thing and do it right. But that voice of the original should somehow still be there, and the original intent should still be there. So if the original writer saw the movie, the writer would say, "Well, that's not what I wrote, but that's what I meant." And if you can do that, I think you've done your job as a screenwriter.

One of our continuing myths was summed up in Huckleberry Finn: Our escape, what we think of as our escape, is that we can always light out for the territories. Well, we really can't, not anymore, but that's part of the American character - that belief that at any moment, I could just drop the coffee cup and disappear. And it makes for a different self-image and a different story, in a way.

In the most basic way, writers are defined not by the stories they tell, or their politics, or their gender, or their race, but by the words they use. Writing begins with language, and it is in that initial choosing, as one sifts through the wayward lushness of our wonderful mongrel English, that choice of vocabulary and grammar and tone, the selection on the palette, that determines who's sitting at that desk. Language creates the writer's attitude toward the particular story he's decided to tell.

New York doesn't exactly have neighborhoods, the way most cities do. What it has is closer to distinct and separate villages, some of them existing on different continents, some of them existing in different centuries, and many of them at war with one another. English is not the primary language in many of these villages, but the Roman alphabet does still have a slight edge.

The British were doing crime stories first, but the British thing is a very different thing. There, the stories are about restoring a break in the fabric of society. The American thing has never been worrying about breaks in the fabric of society, but about people doing their job, whether it's police procedurals or criminals or whatever.

Science fiction is a weird category, because it's the only area of fiction I can think of where the story is not of primary importance. Science fiction tends to be more about the science, or the invention of the fantasy world, or the political allegory. When I left science fiction, I said "They're more interested in planets, and I'm interested in people."

Christmas reminds us we are not alone. We are not unrelated atoms, jouncing and ricocheting amid aliens, but are a part of something, which holds and sustains us. As we struggle with shopping lists and invitations, compounded by December's bad weather, it is good to be reminded that there are people in our lives who are worth this aggravation, and people to whom we are worth the same. Christmas shows us the ties that bind us together, threads of love and caring, woven in the simplest and strongest way within the family.

In the first batch of readers, back in the '60s and '70s, the criminal class was still literate, so I would get letters from people in prison; they thought that I was somebody whom they could shop-talk with, and they would tell me very funny stories. I got a lot of those. Guys who were going to wind up doing 10 to 15 for bank robbery, yes, were reading my books.

Santa Claus is a god. He's no less a god than Ahura Mazda, or Odin, or Zeus. Think of the white beard, the chariot pulled through the air by a breed of animal which doesn't ordinarily fly, the prayers (requests for gifts) which are annually mailed to him and which so baffle the Post Office, the specially-garbed priests in all the department stories. And don't gods reflect their creators' society? The Greeks had a huntress goddess, and gods of agriculture and war and love. What else would we have but a god of giving, of merchandising, and of consumption?

Publishing is the only industry I can think of where most of the employees spend most of their time stating with great self-assurance that they don't know how to do their jobs. "I don't know how to sell this," they explain, frowning, as though it's your fault. "I don't know how to package this. I don't know what the market is for this book. I don't know how we're going to draw attention to this." In most occupations, people try to hide their incompetence; only in publishing is it flaunted as though it were the chief qualification for the job.