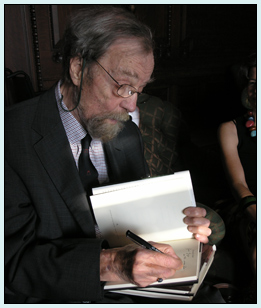

Top 110 Quotes & Sayings by Donald Hall

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American poet Donald Hall.

Last updated on April 21, 2025.

I would work until I got stuck, and I would put it down and pick up something else. I might be able to take a 20-minute nap and get to work again. That way, I was able to work about 10 hours a day... It was important to me to work every day. I managed to work on Christmas day, just to be able to say I worked 365 days a year.

I loathe the trivialization of poetry that happens in creative writing classes. Teachers set exercises to stimulate subject matter: Write a poem about an imaginary landscape with real people in it. Write about a place your parents lived in before you were born. We have enough terrible poetry around without encouraging more of it.

I have written some poetry and two prose books about baseball, but if I had been a rich man, I probably would not have written many of the magazine essays that I have had to do. But, needing to write magazine essays to support myself, I looked to things that I cared about and wanted to write about, and certainly baseball was one of them.