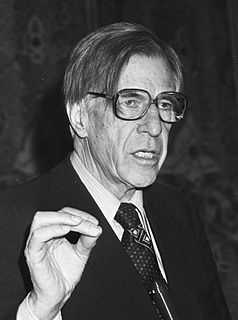

Top 93 Quotes & Sayings by Edmund Phelps

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American economist Edmund Phelps.

Last updated on November 5, 2024.

America's peak years of indigenous innovation ran from the 1820s to the 1960s. There were a few financial panics and two depressions, to be sure. But in this period, a frenzy of creative activity, economic competition and rapid growth in national income provided widening economic inclusion, rising wages for all, and engaging careers for most.

One reason why upturns follow downturns is that downturns tend to overshoot. People get panicky, they're afraid to stay the course, so they start selling. The other thing is that I think, as entrepreneurs keep on waiting to produce new things, that there's an accumulation of as-yet-unexploited new ideas that keeps mounting up.