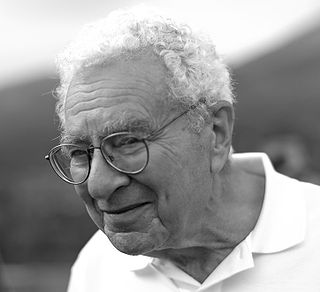

Top 233 Quotes & Sayings by Freeman Dyson - Page 4

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American physicist Freeman Dyson.

Last updated on April 21, 2025.

Now, as Mandelbrot points out, ... Nature has played a joke on the mathematicians. The 19th-century mathematicians may not have been lacking in imagination, but Nature was not. The same pathological structures that the mathematicians invented to break loose from 19th-century naturalism turn out to be inherent in familiar objects all around us.

The bottom line for mathematicians is that the architecture has to be right. In all the mathematics that I did, the essential point was to find the right architecture. It's like building a bridge. Once the main lines of the structure are right, then the details miraculously fit. The problem is the overall design.

The Ph.D. system was designed for a job in academics. And it works really well if you really want to be an academic, and the system actually works quite well. So for people who have the gift and like to go spend their lives as scholars, it's fine. But the trouble is that it's become a kind of a meal ticket - you can't get a job if you don't have a Ph.D.

I'm prejudiced about education altogether. I think it's terribly overrated. It wastes a tremendous amount of time - especially for women, it's particularly badly timed. If they're doing a Ph.D., they have a conflict between raising a family or finishing the degree, which is just at the worst time - between the ages of 25 to 30 or whatever it is. It ruins the five years of their lives.

The thing that makes me most optimistic is China and India - both of them doing well. It's amazing how much progress there's been in China, and also India. Those are the places that really matter - they're half of the world's population. They're the places where things are enormously better now than they were 50 years ago. And I don't see anything that's going to stop that.

You have this world of mathematics, which is very real and which contains all kinds of wonderful stuff. And then we also have the world of nature, which is real, too. And that, by some miracle, the language that nature speaks is the same language that we invented for mathematics. That's just an amazing piece of luck, which we don't understand.

Dropping of the atomic bomb was the main subject of conversation for many years and so people had very strong feelings about it on both sides and people who thought it was the greatest thing they'd ever done and people who thought it was just an unpleasant job and people who thought they should have never done it at all, so there were opinions of all kinds.

Science was blamed for all the horrors of World War I, just as it's blamed today for nuclear weapons and quite rightly. I mean World War I was a horrible war and it was mostly the fault of science, so that was in a way a very bad time for science, but on the other hand we were winning all these Nobel Prizes.

Theory said one thing and the experiment said something different, so that was the stimulus that started me going, that there was something there to be explained, which wasn't understood and to try to see why that experiment gave the answer it did, so it was a big opportunity for a young student starting to have actually an experiment which contradicted the theory, so that's was my chance to understand that.