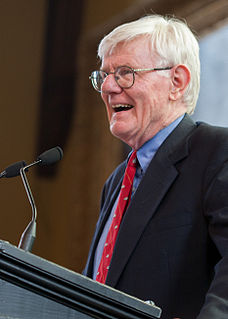

Top 44 Quotes & Sayings by Gordon S. Wood

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American professor Gordon S. Wood.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

As early as 1776, [John Adams] expressed his doubts about America's capacity for virtue. "I have seen all along my Life, Such Selfishness, and Littleness even in New England, that I sometimes tremble to think that, altho We are engaged in the best Cause that ever employed the Human Heart, yet the Prospect of success is doubtfull not for Want of Power or of Wisdom, but of Virtue."

I think [John Adams's] influence on the federal Constitution was indirect. Many including James Madison mocked the first volume of Adams's Defence of the Constitutions of the United States in 1787. But his Massachusetts constitution was a model for those who thought about stable popular governments, with its separation of powers, its bicameral legislature, its independent judiciary, and its strong executive.

[John Adams and Tomas Jefferson] shared experience in 1775 - 1776 in bringing about the separation from Britain and their service in Europe cemented a friendship that in the end withstood the most serious political and religious differences that one could imagine, especially their differences over the French Revolution. It was probably Jefferson's obsession with politeness and civility that kept the relationship from becoming irreparably broken.

This rationale, which justified the mixed constitution of Great Britain, might have made some sense in 1776, but by 1787 most American thinkers had come to believe that all parts of their balanced governments represented in one way or another the sovereign people. They had left the Aristotelian idea of mixed estates - monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy - way behind. [John] Adams had not, and his stubbornness on this point caused him no end of trouble.

Creating senates, the French critics said, implied that there was another social order besides the people represented in the houses of representatives. [John] Adams actually agreed with that implication and argued that the aristocracy and the people had to have separate houses; this was the only way the power of the aristocracy could be contained.

[John Adams] letters courting Abigail Smith are especially priceless. In one of 1764 he addresses her as "Miss Adorable" and says that "By the same Token that the Bearer hereof satt up with you last night I hereby order you to give him, as many Kisses, and as many Hours of your Company after 9 O'Clock as he shall please to Demand and charge them to my Account."

[The Massachusetts constitution] resembles the federal Constitution of 1787 more closely than any of the other revolutionary state constitutions. It was also drawn up by a special convention, and it provided for popular ratification - practices that were followed by the drafters of the federal Constitution of 1787 and subsequent state constitution-makers.

[John] Adams's perception of Europe, and especially France, was clearly different than [Tomas] Jefferson's. For Jefferson, the luxury and sophistication of Europe only made American simplicity and virtue appear dearer. For Adams, by contrast, Europe represented what America was fast becoming - a society consumed by luxury and vice and fundamentally riven by a struggle between rich and poor, gentlemen and commoners.

Deeply versed in history, [John Adams] said over and over that America had no special providence, no special role in history, that Americans were no different from other peoples, that the United States was just as susceptible to viciousness and corruption as any other nation. In this regard, at least, Jefferson's vision has clearly won the day.