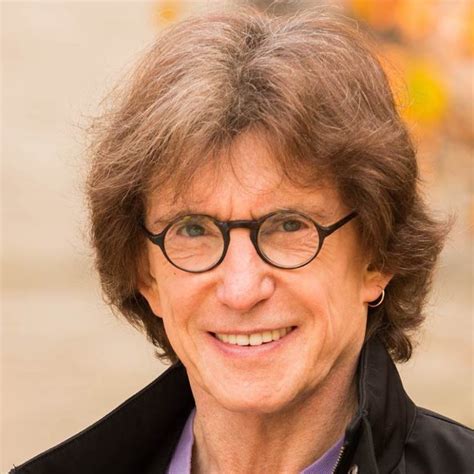

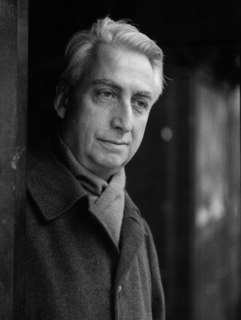

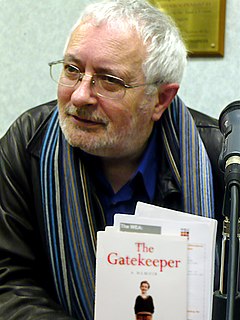

Top 82 Quotes & Sayings by Harold Bloom

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American critic Harold Bloom.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

What is literary tradition? What is a classic? What is a canonical view of tradition? How are canons of accepted classics formed,and how are they unformed? I think that all these quite traditional questions can take one simplistic but still dialectical question as their summing up: do we choose tradition or does it choose us, and why is it necessary that a choosing take place, or a being chosen? What happens if one tries to write, or to teach, or to think, or even to read without the sense of a tradition? Why, nothing at all happens, just nothing.

Reading the very best writers—let us say Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Tolstoy—is not going to make us better citizens. Art is perfectly useless, according to the sublime Oscar Wilde, who was right about everything. He also told us that all bad poetry is sincere. Had I the power to do so, I would command that these words be engraved above every gate at every university, so that each student might ponder the splendor of the insight.

We read deeply for varied reasons, most of them familiar: that we cannot know enough people profoundly enough; that we need to know ourselves better; that we require knowledge, not just of self and others, but of the way things are. Yet the strongest, most authentic motive for deep reading…is the search for a difficult pleasure.

Rebecca Mead's My Life in Middlemarch is a wise, humane, and delightful study of what some regard as the best novel in English. Mead has discovered an original and highly personal way to make herself an inhabitant both of the book and of George Eliot's imaginary city. Though I have read and taught the book these many years I find myself desiring to go back to it after reading Rebecca Mead's work.

The true use of Shakespeare or of Cervantes, of Homer or of Dante, of Chaucer or of Rabelais, is to augment one's own growing inner self. . . . The mind's dialogue with itself is not primarily a social reality. All that the Western Canon can bring one is the proper use of one's own solitude, that solitude whose final form is one's confrontation with one's own mortality.

...the Bible itself is less read than preached, less interpreted than brandished. Increasingly, pastors may drape a limply bound Book over the edges of the pulpit as they depart from it. Members of the congregation carry Bibles to church services; the paster announces a long passage text for his sermon and waits for people to find it, then reads only the first verse of it before he takes off. The Book has become a talisman.

We possess the Canon because we are mortal and also rather belated. There is only so much time, and time must have a stop, while there is more to read than there ever was before. From the Yahwist and Homer to Freud, Kafka, and Beckett is a journey of nearly three millennia. Since that voyage goes past harbors as infinite as Dante, Chaucer, Montaigne, Shakespeare, and Tolstoy, all of whom amply compensate a lifetime's rereadings, we are in the pragmatic dilemma of excluding something else each time we read or reread extensively.

I won't say he [Shakespeare] 'invented' us, because journalists perpetually misunderstand me on that. I'll put it more simply: he contains us. Our ways of thinking and feeling-about ourselves, those we love, those we hate, those we realize are hopelessly 'other' to us-are more shaped by Shakespeare than they are by the experience of our own lives.

People cannot stand the saddest truth I know about the very nature of reading and writing imaginative literature, which is that poetry does not teach us how to talk to other people: it teaches us how to talk to ourselves. What I'm desperately trying to do is to get students to talk to themselves as though they are indeed themselves, and not someone else.

Aesthetic value emanates from the struggle between texts: in the reader, in language, in the classroom, in arguments within a society. Aesthetic value rises out of memory, and so (as Nietzsche saw) out of pain, the pain of surrendering easier pleasures in favour of much more difficult ones ... successful literary works are achieved anxieties, not releases from anxieties.