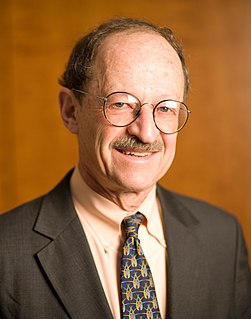

Top 35 Quotes & Sayings by Harold E. Varmus

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American scientist Harold E. Varmus.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

A cancer is not simply a lung cancer. It doesn't simply have a certain kind of appearance under the microscope or a certain behavior, but it also has a set of changes in the genes or in the molecules that modify gene behavior that allows us to categorize cancers in ways that is very useful in thinking about new ways to control cancer by prevention and treatment.