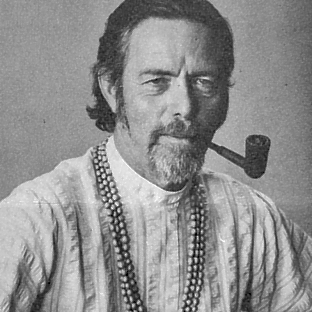

Top 39 Quotes & Sayings by J. L. Austin

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an English philosopher J. L. Austin.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

Our common stock of words embodies all the distinctions men have found worth drawing, and the connexions they have found worth marketing, in the lifetimes of many generation; these surely are likely to be more numerous, more sound, since they have stood up to the long test of thee survival of the fittest, and more subtle, at least in all ordinary and reasonably practical matters, than any that you or I are likely to think up in our arm-chairs of an afternoon-the most favoured alternative method.

Next, 'real' is what we may call a trouser-word. It is usually thought, and I dare say usually rightly thought, that what one might call the affirmative use of a term is basic--that, to understand 'x,' we need to know what it is to be x, or to be an x, and that knowing this apprises us of what it is not to be x, not to be an x. But with 'real' (as we briefly noted earlier) it is the negative use that wears the trousers.

Are cans constitutionally iffy? Whenever, that is, we say that we can do something, or could do something, or could have done something, is there an if in the offing--suppressed, it may be, but due nevertheless to appear when we set out our sentence in full or when we give an explanation of its meaning?

Is it true or false that Belfast is north of London? That the galaxy is the shape of a fried egg? That Beethoven was a drunkard? That Wellington won the battle of Waterloo? There are various degrees and dimensions of success in making statements: the statements fit the facts always more or less loosely, in different ways on different occasions for different intents and purposes.

"What is truth?" said jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer. Pilate was in advance of his time. For "truth" itself is an abstract noun, a camel, that is, of a logical construction, which cannot get past the eye even of a grammarian. We approach it cap and categories in hand: we ask ourselves whether Truth is a substance (the Truth, the Body of Knowledge), or a quality (something like the colour red, inhering in truths), or a relation ("correspondence"). But philosophers should take something more nearly their own size to strain at. What needs discussing rather is the use, or certain uses, of the word "true." In vino, possibly, "veritas," but in a sober symposium "verum."

The trouble is that the expression 'material thing' is functioning already, from the very beginning, simply as a foil for 'sense-datum'; it is not here given, and is never given, any other role to play, and apart from this consideration it would surely never have occurred to anybody to try to represent as some single kind of things the things which the ordinary man says that he 'perceives.

The beginning of sense, not to say wisdom, is to realize that 'doing an action,' as used in philosophy, is a highly abstract expression--it is a stand-in used in the place of any (or almost any?) verb with a personal subject, in the same sort of way that 'thing' is a stand-in for anynoun substantive, and 'quality' a stand-in for the adjective.

Going back into the history of a word, very often into Latin, we come back pretty commonly to pictures or models of how things happen or are done. These models may be fairly sophisticated and recent, as is perhaps the case with 'motive' or 'impulse', but one of the commonest and most primitive types of model is one which is apt to baffle us through its very naturalness and simplicity.

There is no one kind of thing that we 'perceive' but many different kinds, the number being reducible if at all by scientific investigation and not by philosophy: pens are in many ways though not in all ways unlike rainbows, which are in many ways though not in all ways unlike after-images, which in turn are in many ways but not in all ways unlike pictures on the cinema-screen--and so on.