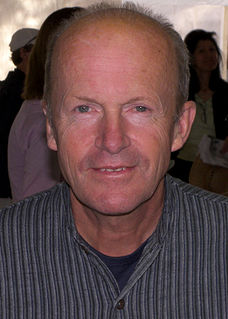

Top 97 Quotes & Sayings by Jim Crace

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an English novelist Jim Crace.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

After 25 years sitting on my own in a room, I was looking for a more companionable job and wanted to work more collaboratively. I've also been very lucky in my career, with good advances and multibook deals. But there is some extent to which I worried that I was writing for the contract and not for the impulse of the thing itself.

If you read the fables, 'Beowulf,' for example, you will know something about the person who writes them, and I like that. Secondly, they will not be about individuals; they will be about community. Thirdly, they're all about moralizing. Fourthly, the way they express themselves takes its tone from the oral tradition.

There is no reason why the Louvre should be your favourite gallery just because it has the grandest collections in France, any more than Kew should necessarily be a favourite garden because it has the largest assemblage of plants, or Tesco your chosen shop because it has the widest variety of canned beans.