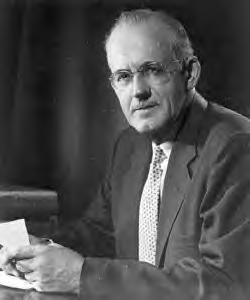

Top 44 Quotes & Sayings by Joseph Butler

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an English priest Joseph Butler.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

People habituate themselves to let things pass through their minds, as one may speak, rather than to think of them. Thus by use they become satisfied merely with seeing what is said, without going any further. Review and attention, and even forming a judgment, becomes fatigue; and to lay anything before them that requires it, is putting them quite out of their way.

Men are impatient, and for precipitating things; but the Author of Nature appears deliberate throughout His operations, accomplishing His natural ends by slow, successive steps. And there is a plan of things beforehand laid out, which, from the nature of it, requires various systems of means, as well as length of time, in order to the carrying on its several parts into execution.