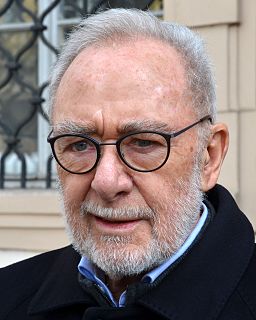

Top 277 Quotes & Sayings by Kehinde Wiley - Page 3

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American artist Kehinde Wiley.

Last updated on December 24, 2024.

I happen to be a twin. I grew up half of my life with someone who looks and sounds like me. And I believe it's possible to hold twin desires in your head, such as the desire to create painting and destroy painting at once. The desire to look at a black American culture as underserved, in need of representation, a desire to mine that said culture and to lay its parts bare and look at it almost clinically.

Let's talk about the artist's desire to go beyond the pictorial or the representational and the desire to create the abstract - the idea that painting can go beyond what is seen. What we found is that, increasingly, painting became about paint, its own material truth. When I'm talking about the way that we look at others and the way that we see ourselves increasingly, looking at others becomes its own material truth.

I had no idea about where I was going. I had no sense of art as anything other than a problem to be fixed, you know, an itch to be scratched. I was in that studio trying my best to feel content with myself. I had, like, a stipend. I had a place to sleep. I had a studio to work in. I had nothing else to think about, you know. And that's - that was a huge luxury in New York City.

If I have the same plan to go into the streets, find random strangers, use art-historical referent from their - from the specific location, to use decorative patterns from this location, that's a rule. That's a set of patterns that you can apply to all societies. But what gives rise or what comes out of each experiment is so radically different.

What came out of that was an intense obsession with status anxiety. So much of these portraits are about fashioning oneself into the image of perfection that ruled the day in the 18th and 19th centuries. It's an antiquated language, but I think we've inherited that language and have forwarded it to its most useful points in the 21st century.

I think didactic art is boring. I mean, I love it in terms of, like, some of the historical precedents that I've learned from. You needed that. We needed those building blocks in terms of - you know, when I look at a great Barbara Kruger, for example, and you're thinking about, you know, the woman's position in society - you know, she found a way of making it beautiful, but at the same time it's very sort of preachy, you know what I mean?

I began working within the streets of Harlem, where, after graduating from Yale [University, New Haven, CT], I became the artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem [New York, NY]. I wanted to know what that was about. I would actually pull people from off of the streets and ask them to come to my studio.

It became a question of taste. I have a certain taste in art history. And that - I had a huge library of art history books in my studio. And I would simply have the models go through those books with me, and we began a conversation about, like, what painting means, why we do it, why people care about it why or how it can mean or make sense today.

There's quite obviously the desire to open the rule sets that allow for inclusion or disclusion. I think that my hope would be that my work set up certain type of precedent, that allowed for great institutions, museums and viewers to see the possibilities of painting culture to be a bit more inclusive.

What we have now is a communication ability. We have the ability to see working ideas that are going on in the great cities throughout the world and whether you live in Shanghai or you live in Sao Paulo, you have the ability of seeing and knowing the ideas of some of the greatest minds of our generation.

It was probably one of the things that gave me a sense of possibility and allowed for me to see beyond the small community that I existed within. You know, I was making friends with young Soviet kids. this is during perestroika. You know, there's bread lines and vodka lines. The entire social structure of what was then the Soviet Union was radically different from what we know today.

I love the of dealing with the homoerotic versus the idea of dealing with certain tropes with regards to black masculinity in the world, propensity towards sports, antisocial behavior, hypersexuality - all of these sort of non-truths that I don't exist in but that I see as being fixed in the world's imagination.

I was trying. I was crawling. I was coming into myself. I was trying to in some ways get beyond - what is the word that I'm looking for? - metaphorical language in painting, and to create something that was more indexical. And what I mean by that is that when you go to the library there's an index card that refers to a book that's actual and real in the world. So that index relates to something real.