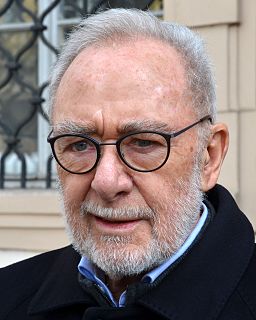

Top 277 Quotes & Sayings by Kehinde Wiley - Page 4

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American artist Kehinde Wiley.

Last updated on April 19, 2025.

I think one of the things that I took from Mel [Bochner] specifically was his ability to look at oneself and one's relationship to the history of art and the practice of art at arm's length, the ability to sort of clinically and coldly remove oneself from the picture and to see it simply as a set of rules, habits, systems, moving parts.

For example, in one of my last exhibitions I had a 50-foot massive painting with I think perhaps a hundred thousand hand-painted small flowers. This was the Christ painting [The Dead Christ in the Tomb, 2008] in my Down exhibition [2008]. Now, I simply can't spend eight hours a day painting small, identical flowers. And so I've got a team that allows me to have these grand, sweeping statements.

That's what I think my job in the world has been, is to sort of try to sit silently a bit and watch it all sort of move and see those small, quiet details, whether it be a small village outside of Colombo [country?] or the favelas of Brazil, where, again, resistance culture is something that you hear resonating in the streets of South Central Los Angeles as well.

I was recently in Israel doing my work and casting for models in the streets of Haifa and Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, meeting young Israelis and Palestinians and Falasha, Ethiopian Jews who had migrated to Israel in the '70s. They're obsessed with Bob Marley. They're obsessed with Kanye West. They're obsessed with resistance culture, people who find that they're not necessarily comfortable in their own personal and national skin.

I pay my models to work with me, so there becomes this weird sort of economic bartering thing, which made me feel really sort of uncomfortable, almost as though you were buying into a situation - which, again, is another way of looking at those paintings. The body language in those paintings is a lot more stiff.

[My twin brother] he was the star artist of the family as we - as we were growing up. He eventually lost interest and went more towards literature and then medicine and then business and so on. But for me it became something that I did well. And it felt great being able to make something look like something.

There's always a joy in newness as a painter, and in sub-Saharan Africa, I encountered different realities with regard to light and how it bounces across the skin. The way that blues and purples come into play. In India and Sri Lanka, it was no different. It became a moment in which I had an opportunity to learn as a painter how to create the body in full form, and that's a very material and aesthetic thing. This is not conceptual. It's all an abstraction.

I think, at the L.A. County Museum of Art, I saw my first example of Kerry James Marshall, who had a very sort of heroic, oversized painting of black men in a barbershop. But it was painted on the same level and with the same urgency that you would see in a grand-scale [Anthony] van Dyck or [Diego] Velazquez. The composition was classically informed; the painting technique was masterful. And it was something that really inspired me because, you know, these were images of young, black men in painting on the museum walls of one of the more sanctified and sacred institutions in Los Angeles.

So much of the hubris that surrounded conceptual art in the 1950s through '70s was that it had this arrogant presupposition that pointing in and of itself was a creative act. It never rigorously politically and socially analyzed the fact that the luxury to point is something that so many people throughout the world don't have.

Like commercial stuff is sort of cheap and disposable and fun and can be sort of interesting in many ways. I love being in popular culture and existing in the evolution of popular culture. But it's so different from painting, and it's so different from that sort of slow, contemplative, gradual process that painting is.

When we talk about Orientalist painting, we're talking about painting generally from the seventeenth through the nineteenth century, and some would say even into the twentieth, that allows Europe to look at Africa, Asia Minor, or East Asia in a way that's revelatory but also as a place in which you can empty yourself out. A place in which there is no place. It's an emptiness and a location at once.

I think that at its best, painting can be an act of juggling perceptions, a hall of mirrors. And it can be a bit confusing and scattering. But as the artist, as the man behind the velvet rope who controls the smoke and the mirrors and the way that things move in the painted space, what I want to do is to try my best to be a good witness.

Much like teaching art to young art students age 10 to 15 or so on, you have to break it down into bite-sized pieces, essential components. You have to - you know, at this point I'm so used to operating within given assumptions about art. But when you're explaining art to art students or people who are new to this experience, you have to really go back to the fundamentals.

In high school I went to the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts. And this is like Fame. It's like that sort of prototypical, dancers in the hallway, theater students, musical students, art geeks. And it was a kindergarten in the truest sense of the world: a children's garden where I was able to sort of really come into myself as an artist, as a person, sexuality issues - like, all of this became something where there was a firming-up and a knowing that went on.

It felt really radically uncomfortable. And I was really not sure at first about releasing that body of work. But then the more I thought about it, the more I thought that that position, that location, is something that's just sort of interesting in its own right, as an experience, as a process. Again, we're talking about this rubric, this set of rules, this grid that I toss on top of different locations globally. This is what came out of Africa.