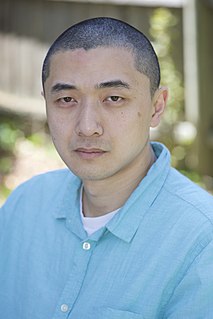

Top 78 Quotes & Sayings by Ken Liu

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American writer Ken Liu.

Last updated on April 19, 2025.

There's this long history of colonialism and the colonial gaze when applied to matters related to China. So a lot of conceptions about China in literary representations in the West are things you can't even fight against because they've been there so long that they've become part of the Western imagination of China.

What tends to happen when people talk about Chinese sci-fi in the West is that there's a lot of projection. We prefer to think of China as a dystopian world that is challenging American hegemony, so we would like to think that Chinese sci-fi is all either militaristic or dystopian. But that's just not the reality of it.

Real history is far more complex and interesting than the simplistic summaries presented in Wikipedia articles. Knowing this allows you to question received wisdom, to challenge 'facts' 'everybody' knows to be true, and to imagine worlds and characters worthy of our rich historical heritage and our complex selves.

The 'Grace of Kings' begins as a very dark, complicated world filled with injustices - among them the oppressed position of women - but gradually transforms into something better through a series of revolutions. But since real social change takes a long time, even by the end of the book, only the seeds of deep change have been planted.

People who are ambitious - politicians who crave power - think that they're in control of it, but at some point, the movement that they started overtakes them, and they lose the ability to direct things anymore, and they become essentially riders on a wild stallion, and wherever the movement goes, wherever power takes them, they have to go along.

I'm conscious of the fact that I'm sort of a bridging figure. I have my Chinese literary heritage and cultural background, so I'm comfortable with these things, but at the same time, I have to navigate the Anglo-American tradition, which has a self-centred view of what Asia and what being Chinese means.