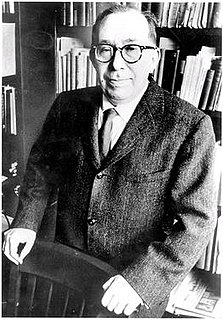

Top 44 Quotes & Sayings by Leo Strauss

Explore popular quotes and sayings by a German philosopher Leo Strauss.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

History teaches us that a given view has been abandoned in favor of another by all men, or by all competent men, or perhaps by only the most vocal men; it does not teach us whether the change was sound or whether the rejected view deserved to be rejected. Only an impartial analysis of the view in question, an analysis that is not dazzled by the victory or stunned by the defeat of the adherents of the view concerned - could teach us anything regarding the worth of the view and hence regarding the meaning of the historical change.

The belief that value judgments are not subject, in the last analysis, to rational control, encourages the inclination to make irresponsible assertions regarding right and wrong or good and bad. One evades discussion of serious issues by the simple device of passing them off as value problems, whereas, to say the least, many of these conflicts arose out of man's very agreement regarding values.

Men are constantly attracted and deluded by two opposite charms: the charm of competence which is engendered by mathematics and everything akin to mathematics, and the charm of humble awe, which is engendered by meditation on the human soul and its experiences. Philosophy is characterized by the gentle, if firm, refusal to succumb to either charm.

We somehow believe that our point of view is superior, higher than those of the greatest minds either because our point of view is that of our time, and our time, being later than the time of the greatest minds, can be presumed to be superior to their times; or else because we believe that each the greatest minds was right from his point of view, but not, as he claims, simply right.

The emancipation of the scholars and scientists from philosophy is according to [Nietzsche] only a part of the democratic movement, i.e. of the emancipation of the low from subordination to the high. ... The plebeian character of the contemporary scholar or scientist is due to the fact that he has no reverence for himself.

Men must always have distinguished (e.g. in judicial matters) between hearsay and seeing with one's own eyes and have preferred what one has seen to what he has merely heard from others. But the use of this distinction was originally limited to particular or subordinate matters. As regards the most weighty matters the first things and the right way the only source of knowledge was hearsay.

Liberal education, which consists in the constant intercourse with the greatest minds, is a training in the highest form of modesty. ... It is at the same time a training in boldness. ... It demands from us the boldness implied in the resolve to regard the accepted views as mere opinions, or to regard the average opinions as extreme opinions which are at least as likely to be wrong as the most strange or least popular opinions

Our understanding of the thought of the past is liable to be the more adequate, the less the historian is convinced of the superiority of his own point of view, or the more he is prepared to admit the possibility that he may have to learn something, not merely about the thinkers of the past, but from them.

To avert the danger [posed by theory] to life, Nietzsche could choose one of two ways: he could insist on the strictly esoteric character of the theoretical analysis of life - that is, restore the Platonic notion of the noble delusion - or else he could deny the possibility of theory proper and so conceive of thought as essentially subservient to, or dependent on, life or fate... If not Nietzsche himself, at any rate his successors [Heidegger] adopted the second alternative.

The most superficial fact regarding the 'Discourses,' the fact that the number of its chapters equals the number of books of Livy's 'History,' compelled us to start a chain of tentative reasoning which brings us suddenly face to face with the only New Testament quotation that ever appears in Machiavelli's two books and with an enormous blasphemy.

According to our social science, we can be or become wise in all matters of secondary importance, but we have to be resigned to utter ignorance in the most important respect: we cannot have any knowledge regarding the ultimate principles of our choices, i.e. regarding their soundness or unsoundness... We are then in the position of beings who are sane and sober when engaged in trivial business and who gamble like madmen when confronted with serious issues.

When speaking of a "body of knowledge" or of "the results of research," e.g., we tacitly assign the same cognitive status to inherited knowledge and to independently acquired knowledge. To counteract this tendency a special effort is required to transform inherited knowledge into genuine knowledge by revitalizing its original discovery, and to discriminate between the genuine and the spurious elements of what claims to be inherited knowledge.

The adjective "political" in "political philosophy" designates not so much the subject matter as a manner of treatment; from this point of view, I say, "political philosophy" means primarily not the philosophic study of politics, but the political, or popular, treatment of philosophy, or the political introduction to philosophy the attempt to lead qualified citizens, or rather their qualified sons, from the political life to the philosophic life.