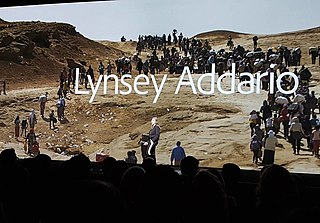

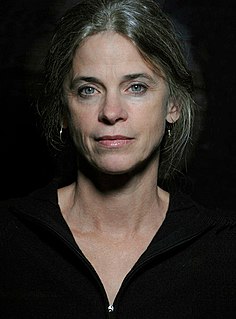

Top 99 Quotes & Sayings by Lynsey Addario

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American photographer Lynsey Addario.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

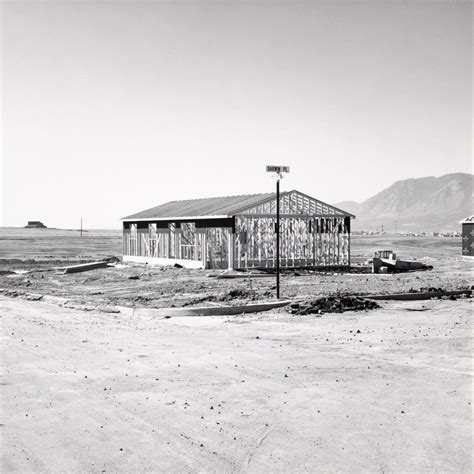

One day I am at home, watching dramatic images of Iraqi Yazidis fleeing for their lives being aired nonstop on 24-hour news channels. Days later, I am there, staring at tens of thousands of displaced Iraqis and feeling a 35-millimeter frame cannot capture the scope of devastation and heartbreak before me.

I do think my childhood is one of the fundamental reasons that I'm able to do my job. We were raised in this totally nonjudgmental family. We never knew who was going to walk in the front door. And as a journalist and a photographer, you walk into so many different scenes that you have to be open to everything.

Let's get one thing straight: I am not an adrenaline junkie. Just because you cover conflict doesn't mean you thrive on adrenaline. It means you have a purpose, and you feel it is very important for people back home to see what is happening on the front line, especially if we are sending American soldiers there.

You have two options when you approach a hostile checkpoint in a war zone, and each is a gamble. The first is to stop and identify yourself as a journalist and hope that you are respected as a neutral observer. The second is to blow past the checkpoint and hope the soldiers guarding it don't open fire on you.

I remember the moment in which we were taken hostage in Libya, and we were asked to lie face down on the ground, and they started putting our arms behind our backs and started tying us up. And we were each begging for our lives because they were deciding whether to execute us, and they had guns to our heads.