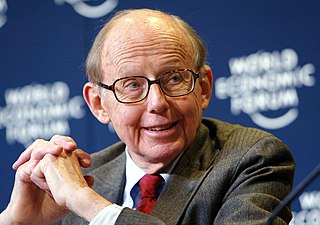

Top 152 Quotes & Sayings by Matthew Desmond - Page 2

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American sociologist Matthew Desmond.

Last updated on April 19, 2025.

You meet folks who are funny and really smart and persistent and loving that are confronting this thing we call poverty, which is just a shorthand for this way of life that holds you underwater. And you just wonder what our country would be if we allowed these people to flourish and reach their full potential.

There were evictions that I saw that I know I'll never forget. In one case, the sheriff and the movers came up on a house full of children. The mom had passed away, and the children had just gone on living there. And the sheriff executed the eviction order - moved the kids' stuff out on the street on a cold, rainy day.

I don't want to sound Pollyannish about this. I understand that poverty is never just poverty. It's often this collection of maladies, this compounded adversity. I'm not naive about the problem. But I think that stable, steady housing is one of the surest footholds we could have on the road to financial stability.