Top 75 Quotes & Sayings by Michael Craig-Martin

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an Irish artist Michael Craig-Martin.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

In the late 70's I started to make drawings of the ordinary objects I had been using in my work. Initially I wanted them to be ready-made drawings of the kind of common objects I had always used in my work. I was surprised to discover I couldn't find the simple, neutral drawings I had assumed existed, so I started to make them myself.

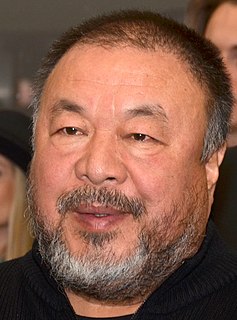

When I was invited to go to Wuhan, I didn't know anything about it, so I looked up the Wikipedia about Wuhan. I discovered that part of Wuhan used to be Hankou, and then I realised that my great grandmother came from Hankou. My grandmother and father were both born in Hankou. Of all the places in China, it is the most amazing place to have asked for my exhibition. I needed to go back where my family comes from!

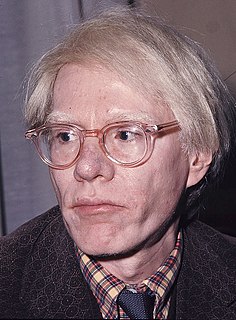

When I was a very young student I loved and admired the work of Sam Beckett, who is famously pessimistic, and whose writing is an extraordinary examination of emptiness. I wanted to be like Beckett. I don't have the same attitude toward the world, I'm naturally optimistic, and so of course I could never be like Beckett. You can't force yourself to become like someone you admire.

I have been using the computer as a work aid since the mid-90's. It is extraordinarily well suited to how I think and work and has transformed my practice. Nearly everything I have done in the past 15 years would have been impossible without it. I use the computer for drawing, composing and colour planning everything, from postage stamps to paintings to architectural-scale installations.

The identifying personal association with objects, which are not personal, is an important modern experience - our real association, the strands of our feelings about the objects that surround us. It's also because they are so familiar, we don't think of them as important in the world, but actually they are the world. We are living in a very material world.

I think that the exchange is very important. Before I did the exhibition in Shanghai, I was a judge for the John Moores Painting Prize and that was very interesting for me, because some of the judges are Chinese and some are British, and we look at the work together. It was fascinating that most of the time we were in complete agreement, but some of the time we were not. People send their works from all over China. For a foreigner, this gave me a very good picture about what is happening in China and its art today.

The internet has extended the possibility of making art to more people, and particularly of enabling it to be seen by others. I am sure the internet is having a profound impact on art, particularly those who have grown up with it, but making good art will remain as difficult (and as easy) as it ever was. Having a lasting impact may become more not less difficult.

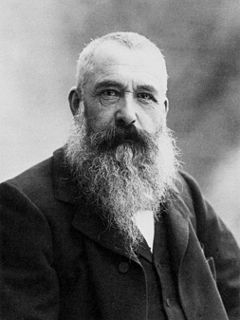

The first exhibition that I used bright colours in painting the room was at a gallery in Paris, and there were seven rooms in the gallery. It was very nice gallery, not very big rooms, around the courtyard, it was a very French space. So I painted each room in different colour. When people came to the exhibition, I saw they came with a smile. Everybody smiles - this is something I never saw in my work before.