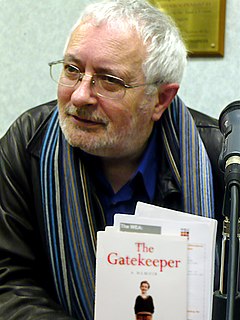

Top 120 Quotes & Sayings by Michael Dirda - Page 2

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American critic Michael Dirda.

Last updated on April 16, 2025.

At 17, I traveled to Mexico in a lemon yellow Mustang and saved money by bunking down in cheap, cockroach-infested flophouses. In my early 20s, I went on to thumb rides through Europe, readily sleeping in train stations, my backpack as a pillow. Once I even hunkered down for a night on a sidewalk grate - for warmth - in Paris.

In truth, my Anglophilia is fundamentally bookish: I yearn for one of those country house libraries, lined on three walls with mahogany bookshelves, their serried splendor interrupted only by enough space to display, above the fireplace, a pair of crossed swords or sculling oars and perhaps a portrait of some great English worthy.

Nearly all the writing of our time is likely to disappear in a hundred years. Certainly most readers - and nearly all critics - feel that [Kurt] Vonnegut started to repeat himself, to grow increasingly self-indulgent and meandering, and to sometimes just blather in his later work. But his books up to "Slaughterhouse-Five" do possess a distinctiveness that will insure some kind of permanence, if only in the history of the 1960s and of science fiction.

In Madame Bovary Flaubert never allows anything to go on too long; he can suggest years of boredom in a paragraph, capture the essence of a character in a single conversational exchange, or show us the gulf between his soulful heroine and her dull-witted husband in a sentence (and one that, moreover, presages all Emma's later experience of men). (...) This is one of the summits of prose art, and not to know such a masterpiece is to live a diminished life.

I have now and again tried to imagine the perfect environment, the ideal conditions for reading: A worn leather armchair on a rainy night? A hammock in a freshly mown backyard? A verandah overlooking the summer sea? Good choices, every one. But I have no doubt that they are all merely displacements, sentimental attempts to replicate the warmth and snugness of my mother's lap.

[Kurt] Vonnegut was a writer whose great gift was that he always seemed to be talking directly to you. He wasn't writing, he wasn't showing off, he was just telling you, nobody else, what it was like, what it was all about. That intimacy made him beloved. We can admire the art of John Updike or Philip Roth, but we love Vonnegut.

Many readers simply can't stomach fantasy. They immediately picture elves with broadswords or mighty-thewed barbarians with battle axes, seeking the bejeweled Coronet of Obeisance ... (But) the best fantasies pull aside the velvet curtain of mere appearance. ... In most instances, fantasy ultimately returns us to our own now re-enchanted world, reminding us that it is neither prosaic nor meaningless, and that how we live and what we do truly matters.

Once we know the plot and its surprises, we can appreciate a book's artistry without the usual confusion and sap flow of emotion, content to follow the action with tenderness and interest, all passion spent. Rather than surrender to the story or the characters - as a good first reader ought - we can now look at how the book works, and instead of swooning over it like a besotted lover begin to appreciate its intricacy and craftmanship. Surprisingly, such dissection doesn't murder the experience. Just the opposite: Only then does a work of art fully live.