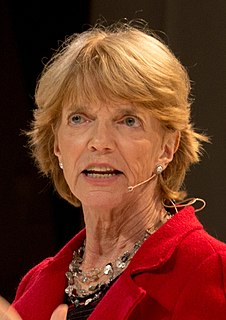

Top 32 Quotes & Sayings by Patricia Churchland

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American philosopher Patricia Churchland.

Last updated on December 21, 2024.

I used to suspect that in the brain, time is its own representation. I now think the problem is so much more complicated. Initially I was rather impressed by the experiments showing that on complex problems, subjects who are distracted do better in getting an answer than either those who answer immediately or those who spend time reflecting on the problem.

It is important to understand that while oxytocin may be the hub of the evolution of the social brain in mammals, it is part of a very complex system. Part of what it does is act in opposition to stress hormones, and in that sense release of oxytocin feels good - as stress hormones and anxiety do not feel good.

Many mammals and birds have systems for strong self-control, and it is not difficult to see why such systems were advantageous and were selected for. Biding your time, deferring gratification, staying still, foregoing sex for safety, and so forth, is essential in getting food, in surviving, and in successful reproduction.

Studies of decision-making in the monkey, where activity of single neurons in parietal cortex is recorded, you can see a lot about the time-accuracy trade-off in the monkey's decision, and you can see from the neuron's activity at what point in his accumulation of evidence he makes his decision to make a particular movement.

I had no idea what philosophy was until I went to college at UBC. I first read Hume and Plato, so naturally I was under the misapprehension that philosophers are trying to figure out what is true, and that contemporary philosophers are mainly trying to figure out what is true about the mind. Of course Hume and Plato were trying to do that, hence my misapprehension.

Early studies of sleep and dreaming were crucially dependent on waking subjects up during sleep to find out whether they are dreaming or not. Using that strategy, it was found that when the eyes are rapidly moving (REM sleep) people are usually dreaming; when the eyes are not moving, there may be some mentation, but little in the way of visually rich dreams.