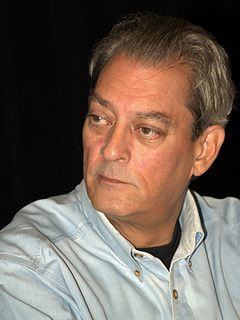

Top 360 Quotes & Sayings by Paul Auster - Page 5

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American author Paul Auster.

Last updated on December 23, 2024.

My children haven't read 'Winter Journal'. They have read some of my work, but I really don't foist it on them. I want them to be free to discover it in their own good time. I think reading an intimate memoir by your father - or an intimate autobiographical work, whatever we want to call this thing - you have to come at it at the right moment, so I'm certainly not foisting it upon them.

Actually, screenplays were much more detailed than what I did in the book In the book I had to invent a style for communicating what the sensation of looking at a film would be, whereas the screenplays I wrote in Paris were actual blueprints for how to do the film, with every gesture, every little movement noted in exhaustive detail.

I thought, "Well, I'm writing about early childhood, so maybe it would make sense to write about late childhood as well, early adulthood." Those were my thoughts, and this was how this crazy book [Winter Journal] was composed. I've never seen a book with pictures like at the end, pictures related to things you've read before.

Autobiographical writings, essays, interviews, various other things... All the non-fiction prose I wanted to keep, that was the idea behind this collected volume, which came out about few years ago. I didn't think of Winter Journal, for example, as an autobiography, or a memoir. What it is is a literary work, composed of autobiographical fragments, but trying to attain, I hope, the effect of music.

A book, at the same time, also has to do with what I call a buzz in the head. It's a certain kind of music that I start hearing. It's the music of the language, but it's also the music of the story. I have to live with that music for a while before I can put any words on the page. I think that's because I have to get my body as much as my mind accustomed to the music of writing that particular book. It really is a mysterious feeling.

In my life, I've lived in very different kinds of places - very tiny rooms when I was young. And you do learn to cope with it. The funny thing is, as you begin to inhabit larger places, it's very interesting how quickly you adapt to your space. What seems enormous at first becomes natural after a few weeks.

I know the pleasure you get from making your films. The intense involvement in every aspect: the acting, the camera, the colors, the costumes, even the hair and makeup. Editing is thrilling. Everything to do with films is absorbing - everything but the money part, the business. But I'm deeply glad I've had that experience.

I don't even own a computer. I write by hand then I type it up on an old manual typewriter. But I cross out a lot - I'm not writing in stone tablets, it's just ink on paper. I don't feel comfortable without a pen or a pencil in my hand. I can't think with my fingers on the keyboard. Words are generated for me by gripping the pen, and pressing the point on the paper.

For example, when I was writing Leviathan, which was written both in New York and in Vermont - I think there were two summers in Vermont, in that house I wrote about in Winter Journal, that broken-down house... I was working in an out-building, a kind of shack, a tumble-down, broken-down mess of a place, and I had a green table. I just thought, "Well, is there a way to bring my life into the fiction I'm writing, will it make a difference?" And the fact is, it doesn't make any difference. It was a kind of experiment which couldn't fail.

My wife is my first reader, my first line of defence I suppose. So she says, "Oh well, oh yes, it's all true." At the same time, I could have written much more about us, but I didn't want to go any further. I did cut things out. There are certain things that I wrote about her that are so gushing with praise and admiration that when I looked at those passages I realised they would be ridiculous to anybody else.

A canteen I remember vividly, and maybe one other thing, I can't remember. And I knew then that he had bought them in an army surplus store that day and he wanted to maybe enhance himself in my eyes, and say, "Well, yes, I have been in the army." Or [he] simply just didn't want to disappoint me. It could have been one or the other. But I knew that he had lied to me. And this filled me with a tremendous sort of anger towards him. At the same time, knowing he was trying to please me, so feeling good about him.

When the father dies, he writes, the son becomes his own father and his own son. He looks at is son and sees himself in the face of the boy. He imagines what the boy sees when he looks at him and finds himself becoming his own father. Inexplicably, he is moved by this. It is not just the sight of the boy that moves him, not even the thought of standing inside his father, but what he sees in the boy of his own vanished past. It is a nostalgia for his own life that he feels, perhaps, a memory of his own boyhood as a son to his father.

I wanted to do something different. Therefore, the first person I thought would have been too exclusionary. It would have said me, me, me, me, me. I, I, I, I, I. As if I were pushing away my experiences from the experiences of others. Because basically what I was trying to do was show our commonality. I mean to say, in the very ordinariness of what I recount I think perhaps the reader will find resonances with his or her own life.

That's all I've ever dreamed of, Mr. Bones. To make the world a better place. To bring some beauty to the drab humdrum corners of the soul. You can do it with a toaster, you can do it with a poem, you can do it by reaching out your hand to a stranger. It doesn't matter what form it takes. To leave the world a little better than you found it. That's the best a man can ever do.