Top 35 Quotes & Sayings by Rashid Johnson

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American photographer Rashid Johnson.

Last updated on April 21, 2025.

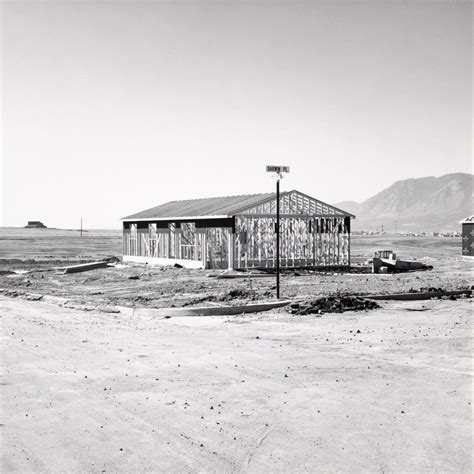

I'd begun to collect things that were lying in piles on the floor of my studio. I had run out of space, and I started to build shelves. I turned around one day and realized that that was the vehicle for carrying so many of the things that I was looking at and talking about, so they went from the walls to the works.