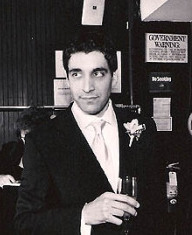

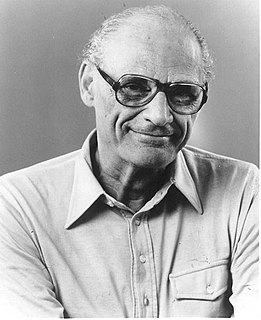

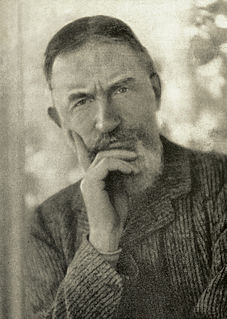

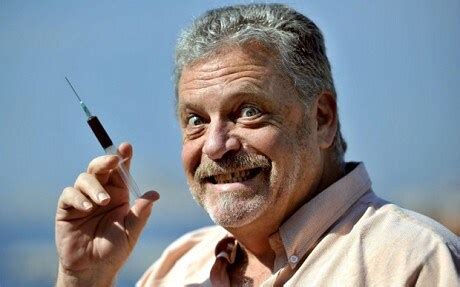

Top 41 Quotes & Sayings by Said Sayrafiezadeh

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American playwright Said Sayrafiezadeh.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

The daily quota I've set for myself is 500 words or approximately a page and a half double-spaced. Which isn't much, except that I'm extremely slow, extremely meticulous. 'Le mot juste' haunts me. On a good day, I will finally secrete the 500th word at about 5 o'clock, and I'll reward myself by going to Housing Works Bookstore to read.

I am haunted by what my life would have been had I not had the courage in my early twenties to leave Pittsburgh for New York City and really commit to being a writer. Pittsburgh is both post-industrial and provincial, and the opportunities there are limited. It would have been quite easy to simply drift through life.

Other families who are poor do what they can to get out of it. My mother did not. She did not utilise her resources. She had a degree. There was something she could have done, but she actively, purposely refused that so we could have this absolutely authentic experience of the worst of capitalism: 'See? Look how bad capitalism is.'

In many ways I'm similar to Barack Obama, who also has a strange name but was raised by a white American mother. His background is far more complicated than his name would suggest. Furthermore, the fact that I was a child during the hostage crisis has caused me to equate being Iranian with being alienated.

I have to expend an awful lot of energy actively undoing the impact of my name. Understandably, people assume that I have at least some connection to Iran. The truth is that I don't. I have very little knowledge about the culture, the language, the history. I've never been to Iran. I've never even been inside a mosque.

I have no personal experience in the military. All I know about it is what I've seen in movies and read in books and watched on television. My knowledge is probably no more or no less than the average person's. 'A Brief Encounter with the Enemy' was created by taking bits and pieces from here and there, and then putting my own spin on them.

While writing my memoir, 'When Skateboards Will Be Free,' I would sometimes have to pore over hours of microfilm at the New York Public Library in order to try to get one obscure detail right. For instance, was the Socialist Workers Party originally called the American Workers Party or the Workers Party of the United States?

My sister married an American and took his name, and my brother has shortened Sayrafiezadeh to Sayraf. So now he's Jacob Sayraf, or sometimes Jake Sayraf. He made the change when he was a teenager, prior to the Iranian revolution and the hostage crisis. So I don't think it was motivated by any anti-Iranian sentiment in the United States.

Since most of the action of the war actually happens off the page (offstage), I wanted to give the characters something they had to contend with on a daily basis, some sort of obstacle. Weather seemed to be the one great equalizer regardless of your station in life - when it snows, everyone is inconvenienced to a certain degree. Plus it's tactile, weather, it affects the skin.

I was trying to hold up a mirror to this country, to reflect the past years or so, and the varying degrees in which we've been affected by the war(s) that doesn't seem to end. And we've all been affected somehow, even if we have no connection to the military, even if we don't know anyone who's killed or been killed. No one escapes something so large.

Love and happiness inextricably combined? I wanted love stories to coincide with war stories, I wanted hope for my characters, I wanted a sense of a future. So do they. So does the reader. But perhaps I shouldn't speak for everyone when I say that love and happiness are interdependent. In my own experience, happiness came with love. Specifically, my wife. That's when my own apathy and stasis ended for good.

This is one of the ways fiction is more liberating than nonfiction - I don't have to be so concerned with fact. I had the paradigm of certain people in my head who became my characters, but I never considered these people to be from a "certain sector of society," unless we agree that we're all from certain sectors of society.

The benefit of writing a collection - as opposed to a novel - is that I'm able to have some version of the war in each story without having to comment on its all-encompassing nature. Turn the page and here are new characters and new situations, but the war remains... Isn't that how life has been for us for over a decade?

An initial impulse of mine was to portray the way in which a city is impacted by war. But this is vague, no? After all, how do you actually have an entire city - or country, for that matter - be a character a reader can follow? One way is by making it smaller and personalizing it, by writing specifically about the citizens and the way they contend with the reality, even minutiae, especially minutiae, of their lives.

Such platitudes as "If you believe it, it will happen," "If you give 100%, you get 100%," "Good things happen to good people" people utter when we don't know what else to say. There's comfort in platitudes, and every so often they're accurate, but mainly they're hollow words. It's a sign of how little we're able to directly address the world around us. The language of the times reveals our avoidance.

But it's hard for me to pinpoint where all my characters and dialogue come from - imagination or real life. My memoir, of course, was all about my past, and many of the short stories cleave very closely to my life, but the more stories I wrote in the collection, the more that seemed to be invented, but who knows... I think I'm writing about a young woman with acne who shoplifts, but I'm really writing about myself.

[Ending] is partly drawn from a desire to shock the audience, to brutally de-romanticize what many Americans think is happening overseas. And partly drawn from my own childhood: violence and a loss of innocence. But keep in mind that, as a writer, I'm both the criminal and the victim. I'm not trying to get out of anything easy.

I sometimes have to write for a while before I figure it out, pretend that I know what I'm doing, sort of like ad-libbing on stage until you remember your line - you hope you sound convincing to the audience. The key is to have enough material, enough threads, so that there's something that can be satisfyingly drawn to a conclusion.