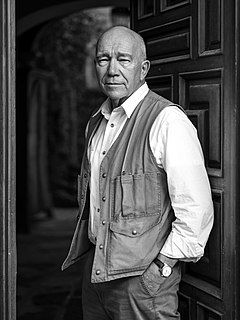

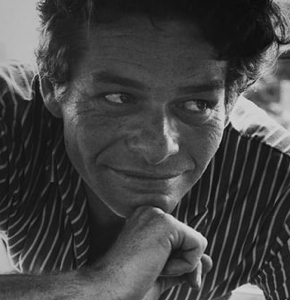

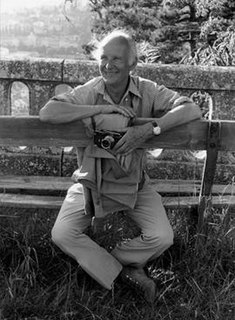

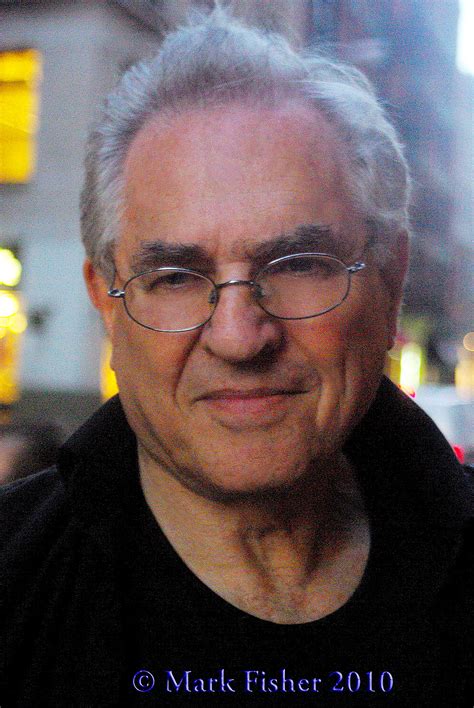

Top 87 Quotes & Sayings by Sam Abell

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American photographer Sam Abell.

Last updated on December 24, 2024.

My parents, grandmother and brother were teachers. My mother taught Latin and French and was the school librarian. My father taught geography and a popular class called Family Living, the precursor to Sociology, which he eventually taught. My grandmother was a beloved one-room school teacher at Knob School, near Sonora in Larue County, Ky.

'Woman on the Plaza,' with its distinct horizon, snow-like surfaces, wintry wall, stunning sunlight, sharp shadows, and hurrying figure, would become the most biographical of my photographs - an abstract image of the landscape and life of northern Ohio where I grew up and first practiced photography.

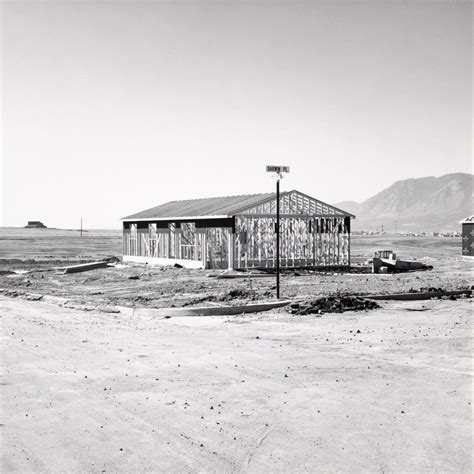

There are grander and more sublime landscapes - to me. There are more compelling cultures. But what appeals to me about central Montana is that the combination of landscape and lifestyle is the most compelling I've seen on this earth. Small mountain ranges and open prairie, and different weather, different light, all within a 360-degree view.

The reason I don't want to say anything about it is it has a strange power to take over the conversation. Just like it's doing with us. I was asked to participate in a documentary about Richard Prince, and be the voice of someone who was appropriated, and I declined. The reason I did is I don't want it to be the subject of the discussion of my work.

One of the things that I most believe in is the compose and wait philosophy of photography. It’s a very satisfying, almost spiritual way to photograph. Life isn't’ knocking you around, life isn't controlling you. You have picked your place, you’ve picked your scene, you’ve picked your light, you’ve done all the decision making and you are waiting for the moment to come to you.

But there is more to a fine photograph than information. We are also seeking to present an image that arouses the curiosity of the viewer or that, best of all, provokes the viewer to think-to ask a question or simply to gaze in thoughtful wonder. We know that photographs inform people. We also know that photographs move people. The photograph that does both is the one we want to see and make. It is the kind of picture that makes you want to pick up your own camera again and go to work.

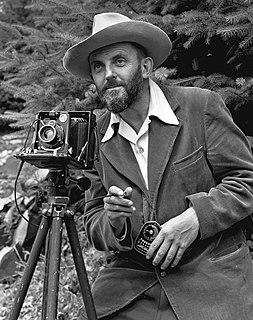

For spiritual companions I have had the many artists who have relied on nature to help shape their imagination. And their most elaborate equipment was a deep reverence for the world through which they passed. Photographers share something with these artists. We seek only to see and to describe with our own voices, and, though we are seldom heard as soloists, we cannot photograph the world in any other way.

My first priority when taking pictures is to achieve clarity. A good documentary photograph transmits the information of the situation with the utmost fidelity; achieving it means understanding the nuances of lighting and composition, and also remembering to keep the lenses clean and the cameras steady.

"You know you are seeing such a photograph if you say to yourself, "I could have taken that picture. I've seen such a scene before, but never like that." It is the kind of photography that relies for its strengths not on special equipment or effects but on the intensity of the photographer's seeing. It is the kind of photography in which the raw materials-light, space, and shape-are arranged in a meaningful and even universal way that gives grace to ordinary objects."

In my first class at the University of Kentucky, my American Literature professor came in, and the first sentence out of his mouth was "The central theme of American Literature is an attempt to reconcile what we've done to the New World." wrote that down in my notebook, and thought, "What is he talking about?" But that's what I think about now. The New World and what we've done to it.

And that desire-the strong desire to take pictures-is important. It borders on a need, based on a habit: the habit of seeing. Whether working or not, photographers are looking, seeing, and thinking about what they see, a habit that is both a pleasure and a problem, for we seldom capture in a single photograph the full expression of what we see and feel. It is the hope that we might express ourselves fully-and the evidence that other photographers have done so-that keep us taking pictures.