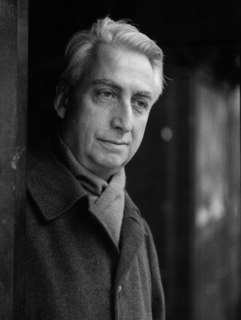

Top 40 Quotes & Sayings by Stephen Greenblatt

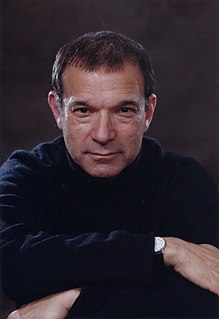

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American critic Stephen Greenblatt.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

A couple of years ago I picked up New Yorker writer Alma Guillermoprieto's "The Heart That Bleeds," which is reportage from Latin America in the 1990s. You can predict that some books will give you a thrill, but you can't predict the books that will hit you hard. It is a little bit like falling in love.

In high school I read [Lev] Tolstoy's "Anna Karenina" and loved it. Then I read [Friedrich] Nietzsche's "On the Genealogy of Morals" and that hit me hard. I don't know where I got it. My parents warned me not to mention either of those books when I went for my college interviews so I wouldn't seem like an egghead. They told me to talk about sports.

There's a huge amount of work on Adam and Eve, from the ancient world to the present. Saint Augustine was obsessed with them.I don't know if it helps my research, but I get a big kick out of Mark Twain, who wrote "The Diaries of Adam and Eve." He wrote very funny stuff on them. I sometimes read things that are loosely related to what I'm thinking and writing about.

A comparably capacious embrace of beauty and pleasure - an embrace that somehow extends to death as well as life, to dissolution as well as creation - characterizes Montaigne's restless reflections on matter in motion, Cervantes's chronicle of his mad knight, Michelangelo's depiction of flayed skin, Leonardo's sketches of whirlpools, Caravaggio's loving attention to the dirty soles of Christ's feet.