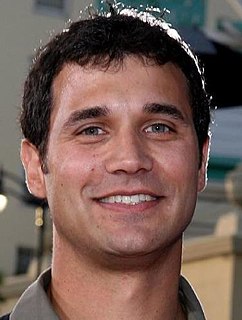

Top 55 Quotes & Sayings by Tod Machover

Explore popular quotes and sayings by a composer Tod Machover.

Last updated on December 21, 2024.

I love silence. And one of the paradoxes about the way I live and also about my work is that definitely one of the reasons I went into music, and especially into composing is that I love setting up an environment where I can be by myself for long periods of time and have everything as quiet as possible, either to think about sound, or to think about ideas, or just to focus on things that are important to me.

I think from age 13, 14, 15, I thought, yes, this rich studio produced music is the future, but it can't be the future to go run away into the recording studio. How can we take that kind of complexity and richness and make it possible for people to touch it and play it live. That's what hyperinstruments are.

The Beatles realized that what they were making in the studio could never be performed. And they had already given up on performing because there were too many screaming fans and they were playing in larger and larger venues so they couldn't even hear what they were playing, it just wasn't any fun any more.

I started thinking, my gosh, all this sophisticated software for measuring how Yo-Yo plays, and how he moves and this technique of the bow, I should be able to use similar techniques for measuring the way anybody moves, and so somebody who is not a professional or a trained musician, I should be able to make a musical environment for them.

it's important as a composer to sit in silence and imagine these complex musical worlds in your head, but it's also a wonderful experience to touch your music and to hear it and hear it in the room with you and to say, you can't have an entire orchestra there, but you'd kind of like to have the orchestra there.

Over my career, I'd say the last 25 years; we've gone from music and computer being for 10 people in the world to having personal computers, to now being able to do amazing things on your iPhone, or with Rock Band. So, right now there's enormous capability with technology in our devices that everybody has access to.

Perhaps 25 to 50 years from now, I can design a piece of music, no so that it appeals to something common in millions of people, but I can design the music so that it's exactly right for you and only you at this particular moment for your particular experience, things that have happened to you over 20 years, to you're particular mental state right now.

I think part of the bad thing is that skill is emphasized so much that a lot of people, by the time they get to Juilliard, well I think they kind of forget why they got into music in the first place and if they're performers - this is a simplification, but a lot of them are trying to win a competition and play more accurately, or better, or more beautifully, whatever can be measured, than somebody else.

I started realizing that one of the great things about opera is that if you make the right kind of story, you can still have this kind of abstract subliminal quality to take you on a journey, but you can root it just enough in a particular situation, a particular kind of real situation that a person might have, or a particular context in the real world.