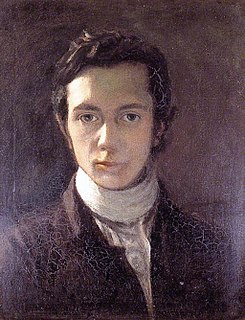

Top 59 Quotes & Sayings by Walter Pater

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an English critic Walter Pater.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

The base of all artistic genius is the power of conceiving humanity in a new, striking, rejoicing way, of putting a happy world ofits own creation in place of the meaner world of common days, of generating around itself an atmosphere with a novel power of refraction, selecting, transforming, recombining the images it transmits, according to the choice of the imaginative intellect. In exercising this power, painting and poetry have a choice of subject almost unlimited.

Beauty, like all other qualities presented to human experience, is relative; and the definition of it becomes unmeaning and useless in proportion to its abstractness. To define beauty not in the most abstract, but in the most concrete terms possible, not to find a universal formula for it, but the formula which expresses most adequately this or that special manifestation of it, is the aim of the true student of aesthetics.

To burn always with this hard, gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life . . . Not the fruit of experience, but experience itself, is the end . . . For art comes to you professing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moments' sake.

That the mere matter of a poem, for instance--its subject, its given incidents or situation; that the mere matter of a picture--the actual circumstances of an event, the actual topography of a landscape--should be nothing without the form, the spirit of the handling, that this form, this mode of handling, should become an end in itself, should penetrate every part of the matter;Mthis is what all art constantly strives after, and achieves in different degrees.

It is with a rush of home-sickness that the thought of death presents itself.... Such sentiment is the eternal stock of all religions, modified indeed by changes of time and place, but indestructible, because its root is so deep in the earth of man's nature. The breath of religious initiators passes over them; a few "rise up with wings as eagles" [Isaiah 40:31], but the broad level of religious life is not permanently changed. Religious progress, like all purely spiritual progress, is confined to a few.

But when reflexion begins to play upon these objects... like some trick of magic each object is loosed into a group of impressions - colour, odour, texture... And if we continue to dwell in thought on this world... the whole scope of observation is dwarfed into the narrow chamber of the individual mind.

She is older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire, she has been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave; and has been a diver in deep seas, and keeps their fallen day about her; and trafficked for strange webs with Eastern merchants, and, as Leda, was the mother of Helen of Troy, and, as Saint Anne, the mother of Mary; and all this has been to her but as the sound of lyres and flutes, and lives only in the delicacy with which it has molded the changing lineaments, and tinged the eyelids and the hands.

For us necessity is not as of old an image without us, with whom we can do warfare; it is a magic web woven through and through us, like that magnetic system of which modern science speaks, penetrating us with a network subtler than our subtlest nerves, yet bearing in it the central forces of the world.

To higher or lower ends, they [the majority of mankind] move too often with something of a sad countenance, with hurried and ignoble gait, becoming, unconsciously, something like thorns, in their anxiety to bear grapes; it being possible for people, in the pursuit of even great ends, to become themselves thin and impoverished in spirit and temper, thus diminishing the sum of perfection in the world, at its very sources.

To burn always with this hard, gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life. ... While all melts under our feet, we may well grasp at any exquisite passion, or any contribution to knowledge that seems by a lifted horizon to set the spirit free for a moment, or any stirring of the senses, strange dyes, strange colours, and curious odours, or work of the artist's hands, or the face of one's friend.

Not to discriminate every moment some passionate attitude in those about us, and in the very brilliancy of their gifts some tragic dividing of forces on their ways, is, on this short day of frost and sun, to sleep before evening. With this sense of the splendour of our experience and of its awful brevity, gathering all we are into one desperate effort to see and touch, we shall hardly have time to make theories about the things we see and touch.

Has nature connected itself together by no bond, allowed itself to be thus crippled, and split into the divine and human elements? Well! there are certain divine powers of a middle nature, through whom our aspirations are conveyed to the gods, and theirs to us. A celestial ladder, a ladder from heaven to earth.