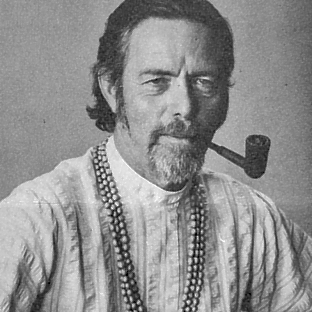

Top 26 Quotes & Sayings by William Ernest Hocking

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American philosopher William Ernest Hocking.

Last updated on April 14, 2025.

For those who have only to obey, law is what the sovereign commands. For the sovereign, in the throes of deciding what he ought to command, this view of law is singularly empty of light and leading. In the dispersed sovereignty of modern states, and especially in times of rapid social change, law must look to the future as well as to history and precedent, and to what is possible and right as well as to what is actual.

Pure community is a matter of no interest to any will; but a community which pursues a common good is of supreme interest to all wills; and what we have here said is that whatever the nature of that common good ... it must contain the development of individual powers, as a prior condition for all other goods.

What our view of the effectiveness of religion in history does at once make evident as to its nature is--first, its necessary distinction; second, its necessary supremacy. These characters though external have been so essential to its fruitfulness, as to justify the statement that without them religion is not religion. A merged religion and a negligible or subordinate religion are no religion.

This merely formal conceiving of the facts of one's own wretchedness is at the same time a departure from them--placing them in the object. It is not idle, therefore, to observe reflexively that in that very Thought, one has separated himself from them, and is no longer that which empirically he still sees himself to be.

A person who wills to have a good will, already has a good will--in its rudiments. There is solid satisfaction in knowing that the mere desire to get out of an old habit is a material advance upon the condition of submergence in that habit. The longest step toward cleanliness is made when one gains--nothing but dissatisfaction with dirt.

Wherever moral ambition exists, there right exists. And moral ambition itself must be presumed present in subconsciousness, even when the conscious self seems to reject it, so long as society has resources for bringing it into action; in much the same way that the life-saver presumes life to exist in the drowned man until he has exhausted his resources for recovering respiration.

We are driven to confess that we actually care more for religion than we do for religious theories and ideas: and in merely making that distinction between religion and its doctrine-elements, have we not already relegated the latter to an external and subordinate position? Have we not asserted that "religion itself" has some other essence or constitution than mere idea or thought?