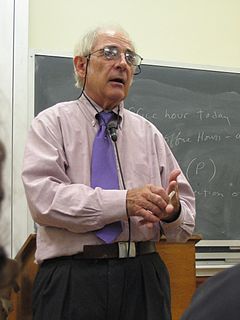

Top 39 Quotes & Sayings by John Searle

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American philosopher John Searle.

Last updated on December 25, 2024.

Because we do not understand the brain very well we are constantly tempted to use the latest technology as a model for trying to understand it. In my childhood we were always assured that the brain was a telephone switchboard...Sherrington, the great British neuroscientist, thought the brain worked like a telegraph system. Freud often compared the brain to hydraulic and electromagnetic systems. Leibniz compared it to a mill...At present, obviously, the metaphor is the digital computer.

It seemed to a number of philosophers of language, myself included, that we should attempt to achieve a unification of Chomsky's syntax, with the results of the researches that were going on in semantics and pragmatics. I believe that this effort has proven to be a failure. Though Chomsky did indeed revolutionize the subject of linguistics, it is not at all clear, at the end the century, what the solid results of this revolution are. As far as I can tell there is not a single rule of syntax that all, or even most, competent linguists are prepared to agree is a rule.

Darwin's greatest achievement was to show that the appearance of purpose, planning, teleology (design), and intentionality in the origin and development of human and animal species was entirely an illusion. The illusion could be explained by evolutionary processes that contained no such purpose at all. But the spread of ideas through imitation required the whole apparatus of human consciousness and intentionality

The general nature of the speech act fallacy can be stated as follows, using "good" as our example. Calling something good is characteristically praising or commending or recommending it, etc. But it is a fallacy to infer from this that the meaning of "good" is explained by saying it is used to perform the act of commendation.

In the performance of an illocutionary act in the literal utterance of a sentence, the speaker intends to produce a certain effect by means of getting the hearer to recognize his intention to produce that effect; and furthermore, if he is using the words literally, he intends this recognition to be achieved in virtue of the fact that the rules for using the expressions he utters associate the expression with the production of that effect.

It seems to me obvious that infants and many animals that do not in any ordinary sense have a language or perform speech acts nonetheless have Intentional states. Only someone in the grip of a philosophical theory would deny that small babies can literally be said to want milk and that dogs want to be let out or believe that their master is at the door.