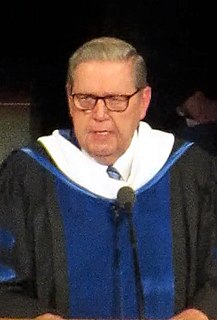

Top 45 Quotes & Sayings by John Yoo

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American educator John Yoo.

Last updated on November 25, 2024.

The United States of course wants to follow the highest standards of conduct with regard to enemy combatants who follow the rules of war. It should and does follow the Geneva Conventions scrupulously when fighting the armed forces of other nations that have signed the Geneva Conventions or follow their principles.

Congress has created and funded a huge peacetime military that has substantial abilities to wage offensive operations, and it has not placed restrictions on the use of that military or the funds to support it, because it would rather let the president take the political risks in deciding on war. If Congress wanted to play a role in restricting war, it could - it simply does not want to. But we should not mistake a failure of political will for a violation of the Constitution.

An American leader would be derelict of duty if he did not seek to understand all his options in such unprecedented circumstances. Presidents Lincoln during the Civil War and Roosevelt in the lead-up to World War II sought legal advice about the outer bounds of their power - even if they did not always use it. Our leaders should ask legal questions first, before setting policy or making decisions in a fog of uncertainty.

I think it can be very important for the president to seek congressional approval for war , even though not constitutionally required to do so, in certain situations. It makes sense to go to Congress to signal our national resolve and our willingness to fight to defend other nations or the freedom of their peoples.

The United States is at war with the al Qaeda terrorist group. Al Qaeda is not a nation-state and it has not signed the Geneva Conventions. It shows no desire to obey the laws of war; if anything it directly violates them by disguising themselves as civilians and attacking purely civilian targets to cause massive casualties.

It is easy now for critics to claim that the work was poor; they haven't produced their own analyses or confronted any of the hard questions. For example, would they say that no technique beyond shouted questions could be used to interrogate a high-level terrorist leader, such as Osama bin Laden, who knows of planned attacks on the United States?

Unlike previous wars, our enemy now is a stateless network of religious extremists. They do not obey the laws of war, they hide among peaceful populations and launch surprise attacks on civilians. They have no armed forces per se, no territory or citizens to defend and no fear of dying during their attacks. Information is our primary weapon against this enemy, and intelligence gathered from captured operatives is perhaps the most effective means of preventing future attacks.

There are pros and cons about the policy decision whether to follow the Geneva Conventions in a war where they do not legally apply. Among the pros might be benefits for America's image, its ability to argue in future conflicts that the Conventions should be followed, and training soldiers to follow only the Geneva standards. Among the cons might be greater security and safety for our troops who capture and detain al Qaeda operatives and the ability to gather more actionable intelligence swiftly.

I believe that the power to declare war is most important in limiting the powers of the national government in regard to the rights of its citizens, but that it does not require Congress to give its approval before the president uses force abroad. I do not believe that the framers of the Constitution understood the power to declare to mean "authorize" or "commence" war. That does not mean that the separation of powers or checks and balances will not work.