Top 152 Quotes & Sayings by Matthew Desmond

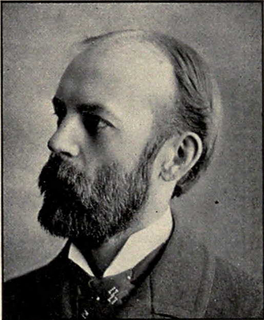

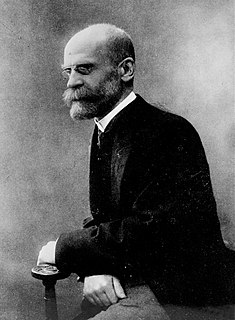

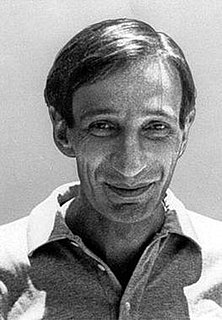

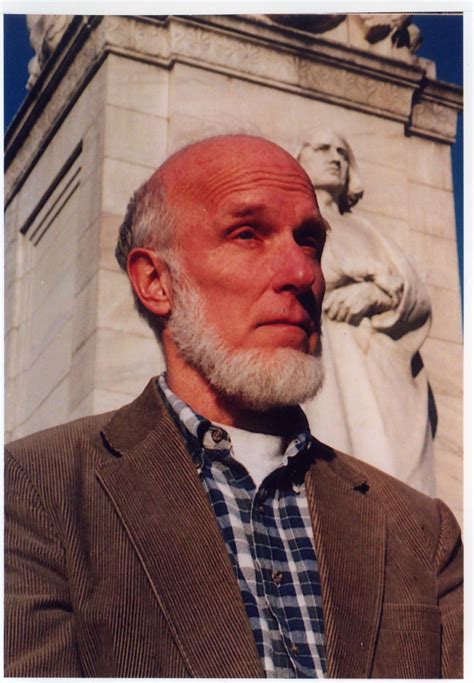

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American sociologist Matthew Desmond.

Last updated on November 25, 2024.

The standard of 'affordable' housing is that which costs roughly 30 percent or less of a family's income. Because of rising housing costs and stagnant wages, slightly more than half of all poor renting families in the country spend more than 50 percent of their income on housing costs, and at least one in four spends more than 70 percent.