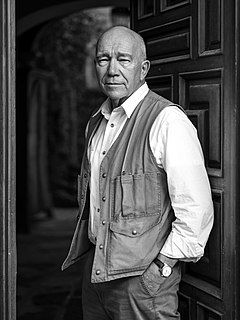

Top 103 Quotes & Sayings by Robert Adams - Page 2

Explore popular quotes and sayings by an American photographer Robert Adams.

Last updated on November 5, 2024.

Little wonder that we. . .find the old pictures of openness - pictures usually without any blur, and made by what seems a ritual of patience - wonderful. They restore to us knowledge of a place we seek but lose in the rush of our search. Though to enjoy even the pictures, much less the space itself, requires that we be still longer than is our custom.

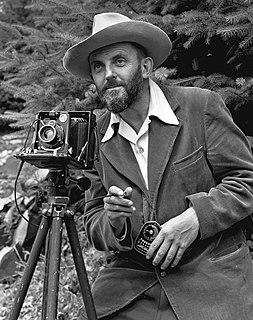

... If we consider the difference between William Henry Jackson packing in his camera by mule, and the person stepping for a moment from his car to take a picture with his Instamatic, it becomes clear how some of our space has vanished; if the time it takes to cross space is a way by which we define it, then to arrive at a view of space 'in no time' is to have denied its reality.

Still photographs often differ from life more by their silence than by the immobility of their subjects. Landscape pictures tend to converge with life, however, on summer nights, when the sounds outside, after we call in children and close garage doors, are small - the whir of moths, the snap of a stick.

In a foreign country it is far from easy to study a scene at length when you know that at any minute someone may appear and ask what you are doing and that you can't answer, and you haven't many references, and you don't know the law. Neither is it easy to find and know the subjects for portraits or comfortable to make such picture when you cannot apply an anesthesia of small talk.

C.S. Lewis admitted, when he was asked to set forth his beliefs, that he never felt less sure of them than when he tried to speak of them. Photographers know this frailty. To them words are a pallid, diffuse way of describing and celebrating what matters. Their gift is to see what will be affecting as a print. Mute.

Part of the reason that these attempts at explanation fail, I think, is that photographers, like all artists, choose their medium because it allows them the most fully truthful expression of their vision... as Robert Frost told a person who asked him what one of his poems meant, 'You want me to say it worse?'

Why do most great pictures look uncontrived? Why do photographers bother with the deception, especially since it so often requires the hardest work of all? The answer is, I think, that the deception is necessary if the goal of art is to be reached: only pictures that look as if they had been easily made can convincingly suggest that beauty is commonplace.

Part of the difficulty in trying to be both an artist and a businessperson is this: You make a picture because you have seen something beyond price; then you are to turn and assign to your record of it a cash value. If the selling is not necessarily a contradiction of the truth in the picture, it is so close to being a contradiction—and the truth is always in shades of gray-that you are worn down by the threat.

Landscape pictures can offer us, I think, three verities: geography, autobiography, and metaphor. Geography is, if taken alone, sometimes boring, autobiography is frequently trivial, and metaphor can be dubious. But taken together, as in the best work of people like Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston, the three kinds of information strengthen each other and reinforce what we all work to keep intact - the affection for life.

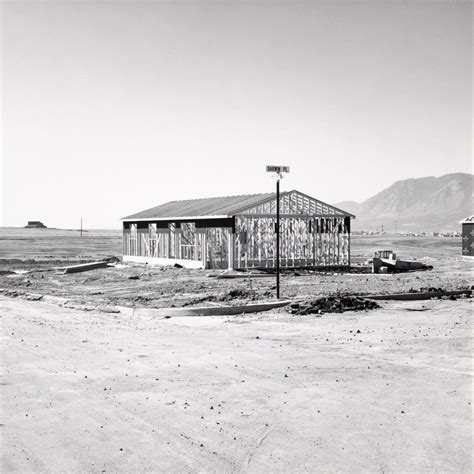

The suburban West is, from a moral perspective, depressing evidence that we have misused our freedom. There is, however, another aspect to the landscape, an unexpected glory. Over the cheap tracts and littered arroyos one sometimes see a light as clean as that recorded by O'Sullivan. Since it owes nothing to our care, it is an assurance; beauty is final.