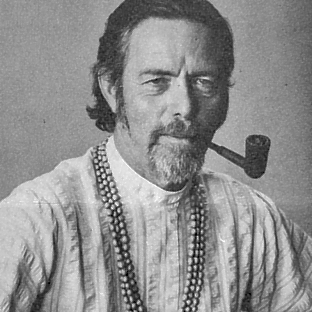

A Quote by Bernard de Mandeville

This laudable quality is commonly known by the name of Manners and Good-breeding, and consists in a Fashionable Habit, acquir'd by Precept and Example, of flattering the Pride and Selfishness of others, and concealing our own with Judgment and Dexterity.

Related Quotes

There are cultures in which it is believed that a name contains all a persons mystical power. That a name should be known only to God and to the person who holds it and to very few privileged others. To pronounce such a name either ones own or someone else's is to invite jeopardy. This it seemed was such a name.