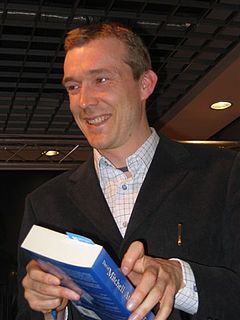

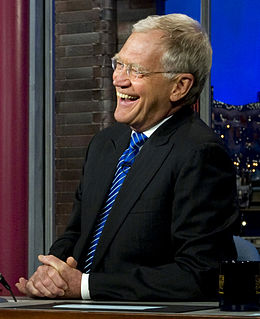

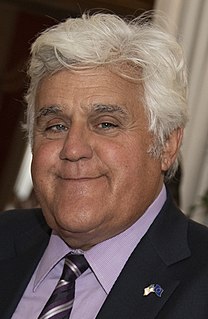

A Quote by Bob Newhart

Stammering is different than stuttering. Stutterers have trouble with the letters, while stammerers trip over entire parts of a sentence. We stammerers generally think of ourselves as very bright. My own private theory is that stammerers have so many ideas swirling around their brains at once that they can't get them all out, though I haven't found any scientific evidence to back that up.

Related Quotes

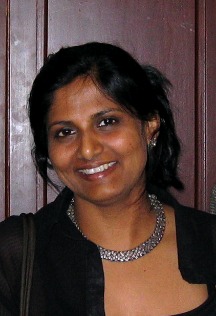

I still have a stammer. I hate it; I loathe and despise it. But it's always there, and I have lots of ways to conceal it. I can conceal it now but I'm not good on the telephone. I get my husband to make dentist appointments. And I hate live radio. Hate it. I really try to avoid it at all costs. But it's always there. Stammerers become skilled at sentence construction and synonyms: we have to be. Faced with a problem word, we need to have instant access to eight others we could use instead - ones we could say without stumbling. I think my stammer is a huge part of my being a writer.

I wish there was a serious investigation into flying saucers that wasn't conducted by crackpots. Unfortunately nearly all of the people who are interested in them kind of manufacture the evidence to fit the theories rather than the other way around. So it's very hard to find any dispassionate treatment of them. Maybe there isn't any scientific basis in which case that's why you never see any scientific evidence.

I turn sentences around. That's my life. I write a sentence and then I turn it around. Then I look at it and I turn it around again. Then I have lunch. Then I come back in and write another sentence. Then I have tea and turn the new sentence around. Then I read the two sentences over and turn them both around. Then I lie down on my sofa and think. Then I get up and throw them out and start from the beginning.

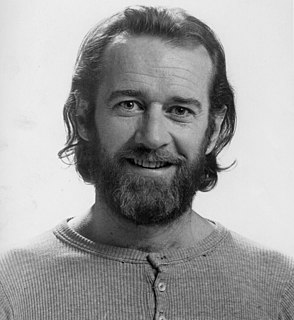

I think stutterers are funny. And I know it's rude and politically incorrect to laugh at stutterers. But I think it is okay because I know why they're funny. They make people nervous. People think, when on earth are they going to get the word out, so they start laughing out of their own nervousness.

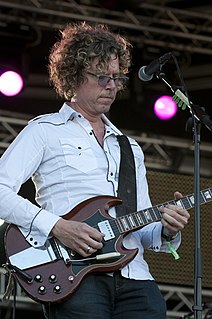

If anything, my problem is, I'm not a genius, it's just that I can write songs very quick. I have a lot of ideas, let's put it that way - I have too many ideas. And my problem is, I stockpile ideas and I get lazy and I don't finish them, and next thing I know, I'm looking around and I've got a hundred song ideas, but are any of them any good? I don't know.

Evidence-based reasoning underpins all scientific thinking, and it involves testing hypotheses or theories against data. Validating a theory requires replicable measurements from independent groups with different equipment and methods of analysis. Convergence of evidence is critical to the acceptance of a scientific idea.

I think there is something exhilarating in flying amongst clouds, and always get a feeling of wanting to pit my aeroplane against them, charge at them, climb over them to show them you have them beat, circle round them, and generally play with them; but clouds can on occasion hold their own against the aviator, and many a pilot has found himself emerging from a cloud not on a level keel.

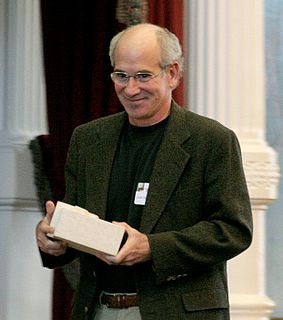

I think '300 Arguments' is a real tiny wallop of a book. It looks very slim, and at first, each little two-sentence or one-sentence thing kind of stands on its own, but again, as you read it, you get sucked into the momentum of it, and the whole of it is much larger than the sum of its parts in a really beautiful way.

Our moment had passed somehow. I was different. He was, too. Without our “madness” to unite us, there wasn’t anything much there. Or maybe too much had happened in too short a time. It’s like when you take a trip with someone you don’t know very well. Sometimes you can get very close very quickly, but then after the trip is over, you realise all that was a false sort of closeness. An intimacy based on the trip more than the travellers, if that makes any sense.

I never think of an entire book at once. I always just start with a very small idea. In 'Holes,' I just began with the setting; a juvenile correctional facility located in the Texas desert. Then I slowly make up the story, and rewrite it several times, and each time I rewrite it, I get new ideas, and change the old ideas around.