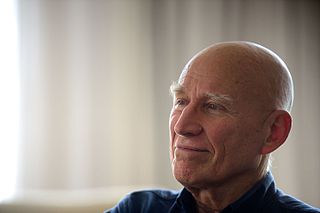

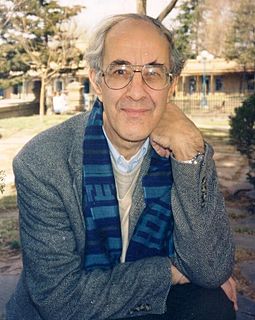

A Quote by Brian Greene

That is, you can have nothingness, absolute nothingness for maybe a tiny fraction of a second, if a second can be defined in that arena, but then it falls apart into a something and an anti-something. And that something is then what we call the universe. But can we really understand that or put rigorous mathematics or testable experiments against that? Not yet. So one of the big holy grail of physics is to understand why there is something rather than nothing.

Related Quotes

What do you mean less than nothing? I don't think there is any such thing as less than nothing. Nothing is absolutely the limit of nothingness. It's the lowest you can go. It's the end of the line. How can something be less than nothing? If there were something that was less than nothing, then nothing would not be nothing, it would be something - even though it's just a very little bit of something. But if nothing is nothing, then nothing has nothing that is less than it is.

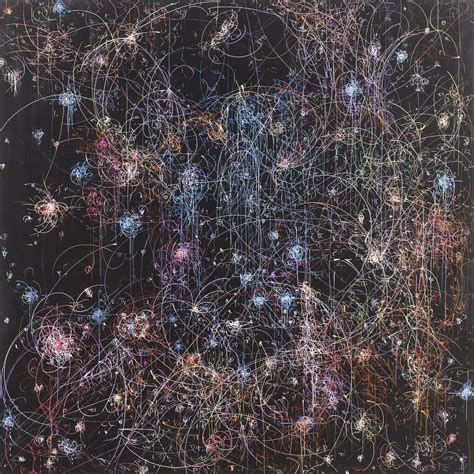

A scenario is suggested by which the universe and its laws could have arisen naturally from nothing. Current cosmology suggests that no laws of physics were violated in bringing the universe into existence. The laws of physics themselves are shown to correspond to what one would expect if the universe appeared from nothing. There is something rather than nothing because something is more stable.

I would then say that there are two kinds of feeling. The first is to feel in the sense of concentrating your emotions on something immediately available for your understanding: you make your understanding out of the emotions you have about it. The second is to feel in the sense of being affected without trying to understand: something is felt, you do not know what, and it is more important to feel it than to try to understand it, since once you try to understand it you no longer feel it.

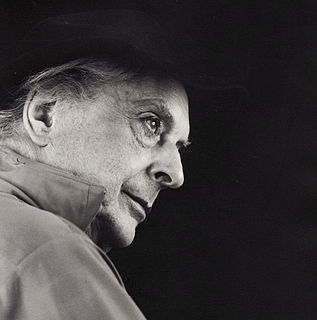

I have a way to photograph. You work with space, you have a camera, you have a frame, and then a fraction of a second. It's very instinctive. What you do is a fraction of a second, it's there and it's not there. But in this fraction of a second comes your past, comes your future, comes your relation with people, comes your ideology, comes your hate, comes your love - all together in this fraction of a second, it materializes there.

From somewhere, back in my youth, heard Prof say, 'Manuel, when faced with a problem you do not understand, do any part of it you do understand, then look at it again.' He had been teaching me something he himself did not understand very well—something in math—but had taught me something far more important, a basic principle.

It is this nothingness (in solitude) that I have to face in my solitude, a nothingness so dreadful that everything in me wants to run to my friends, my work, and my distractions so that I can forget my nothingness and make myself believe that I am worth something. The task is to persevere in my solitude, to stay in my cell until all my seductive visitors get tired of pounding on my door and leave me alone. The wisdom of the desert is that the confrontation with our own frightening nothingness forces us to surrender ourselves totally and unconditionally to the Lord Jesus Christ.

I know our culture will sometimes understand a love for Jesus as weakness. There is this lie floating around that says I am supposed to be able to do life alone, without any help, without stopping to worship something bigger than myself. But I actually believe there is something bigger than me, and I need for there to be something bigger than me. I need someone to put awe inside me; I need to come second to someone who has everything figured out.