A Quote by Ha-Joon Chang

Contrary to what professional economists will typically tell you, economics is not a science. All economic theories have underlying political and ethical assumptions, which make it impossible to prove them right or wrong in the way we can with theories in physics or chemistry.

Related Quotes

Even mistaken hypotheses and theories are of use in leading to discoveries. This remark is true in all the sciences. The alchemists founded chemistry by pursuing chimerical problems and theories which are false. In physical science, which is more advanced than biology, we might still cite men of science who make great discoveries by relying on false theories.

It is ... a sign of the times-though our brothers of physics and chemistry may smile to hear me say so-that biology is now a science in which theories can be devised: theories which lead to predictions and predictions which sometimes turn out to be correct. These facts confirm me in a belief I hold most passionately-that biology is the heir of all the sciences.

Newton's theory is not 'not right', it just does not cover all distances. Contrary to popular belief, theories in science are not proven wrong, they are just replaced by more complete and convenient theories. To sound provocative, even the geocentric theory was never "proven" wrong, it is just not as convenient as the heliocentric theory, since it requires endless epicycles.

Because those who hold conspiracy theories typically suffer from a crippled epistemology, in accordance with which it is rational to hold such theories, the best response consists in cognitive infiltration of extremist groups. Various policy dilemmas, such as the question whether it is better for government to rebut conspiracy theories or to ignore them, are explored in this light.

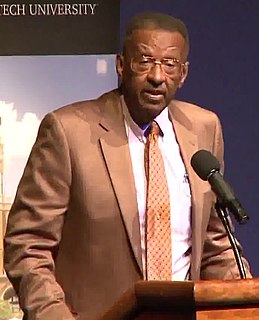

History has got a lot to do with unique circumstances under certain particular cases and grand theories will always find counter cases. I don't think that people whose expertise lies in one thing should try to make grand theories about something (a) where it's very hard to get the evidence to prove that you're right and (b) where it's much too easy to make up stories that seem right.

Managers are already voracious consumers of theory. Every time they make a decision or take action, it's based on some theory that leads them to believe that action will lead to the right result. The problem is, most managers aren't aware of the theories they're using, and they often use the wrong theories for the situation.

One of the ways of stopping science would be only to do experiments in the region where you know the law. But experimenters search most diligently, and with the greatest effort, in exactly those places where it seems most likely that we can prove our theories wrong. In other words, we are trying to prove ourselves wrong as quickly as possible, because only in that way can we find progress.

Our minds are specifically adapted to developing certain theories, and we have a science if the theories that are available to our minds happen to be close to true. Well, there is no particular reason to suppose that the intersection of true theories and theories that are accessible to the mind is very large. It may not be very large.

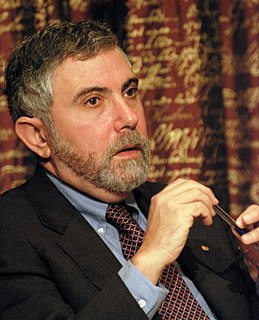

I write with two things in mind. I want to be right with my fellow economists. After all, I've made my life as a professional economist, so I'm careful that my economics is as it should be. But I have long felt that there's no economic proposition that can't be stated in clear, accessible language. So I try to be right with my fellow economists, but I try to have an audience of any interested, intelligent person.