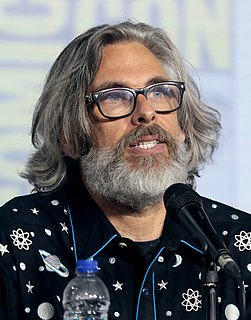

A Quote by John Scalzi

I tell people the first time I decided to write a novel I was in my mid-20s, and it was, 'Well, it's time to see if I can do this.' I basically flipped a coin to see if I was going to write science fiction or if I was going to do a crime novel. The coin toss went to science fiction.