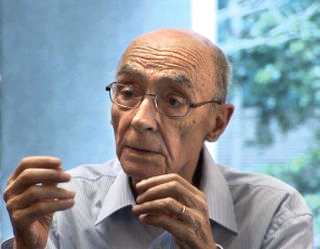

A Quote by Jose Saramago

I think the novel is not so much a literary genre, but a literary space, like a sea that is filled by many rivers. The novel receives streams of science, philosophy, poetry and contains all of these; it's not simply telling a story.

Related Quotes

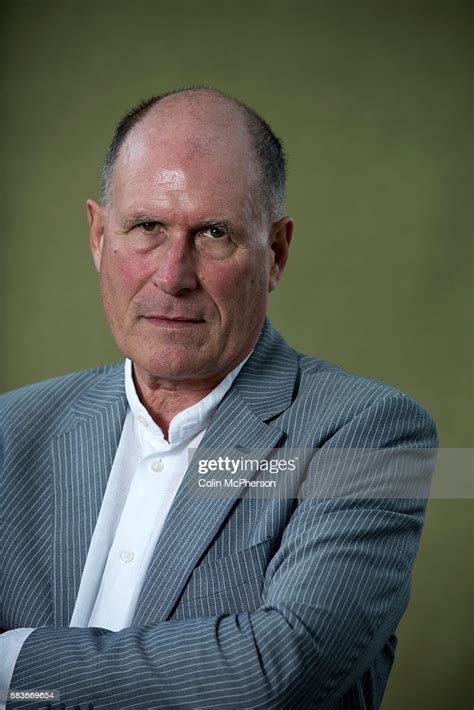

Madly, futilely, I wrote novel after novel, eight in all, that failed to find a publisher. I persisted because for me the novel was the supreme literary form: not just one among many, not a relic of the past, but the way we communicate to one another the subtlest truths about this business of living.

Madly, futilely, I wrote novel after novel, eight in all, that failed to find a publisher. I persisted because for me the novel was the supreme literary form - not just one among many, not a relic of the past, but the way we communicate to one another the subtlest truths about this business of living.

There is something essential and necessary about the immediacy and democracy of poetry. If you look at the history of literature, poetry is the one enduring genre from Homer to Ashbery - no other literary form has lasted as long. The novel is only two or three hundred years old... And yes, it's mainstream if we look back, we often turn to poetry to encapsulate what was going on in a particular moment because it crystalizes the experience in a very condensed and meaningful way.

One of my favorite literary theorists, Mikhail Bakhtin, wrote that the defining characteristic of the novel is its unprecedented level of "heteroglossia" - the way it brings together so many different registers of language. He doesn't mean national languages, but rather the sublanguages we all navigate between every day: high language, low language, everything. I think there's something really powerful about the idea of the novel as a space that can bring all these languages together - not just aggregate them, like the Internet is so good at doing, but bring them into a dialogue.

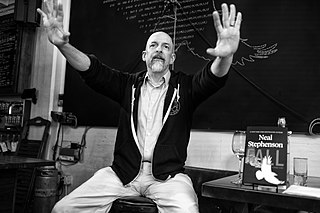

But I'm not a small-literary-novel kind of guy, and once I'd developed the world in the first couple of hundred pages, I felt that there was potential here to go on and write an engaging story set in that world. So that's what I did. This probably ruins things both for the people who want small literary novels and for those who want action-packed epics, but anyway, it's what I wrote.

[Michael] Chabon, who is himself a brash and playful and ebullient genre-bender, writes about how our idea of what constitutes literary fiction is a very narrow idea that, world-historically, evolved over the last sixty or seventy years or so - that until the rise of that kind of third-person-limited, middle-aged-white-guy-experiencing-enlightenment story as in some way the epitome of literary fiction - before that all kinds of crazy things that we would now define as belonging to genre were part of the literary canon.