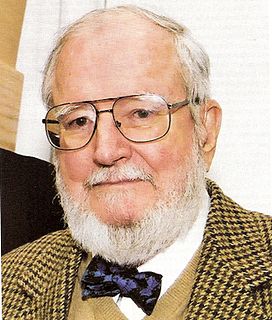

A Quote by Matthew Pearl

The book I'm working on next, which will be my fifth, returns to literary history. I really do love literary history, and I have plenty more ideas on it.

Related Quotes

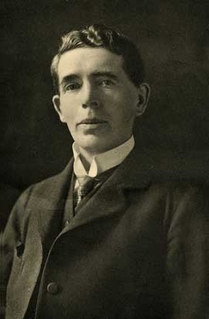

I may remind you that history is not a branch of literature. The facts of history, like the facts of geology or astronomy, can supply material for literary art; for manifest reasons they lend themselves to artistic representation far more readily than those of the natural sciences; but to clothe the story of human society in a literary dress is no more the part of a historian as a historian, than it is the part of an astronomer as an astronomer to present in an artistic shape the story of the stars.

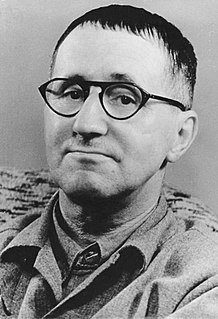

My literary criticism has become less specifically academic. I was really writing literary history in The New Poetic, but my general practice of writing literary criticism is pretty much what it always has been. And there has always been a strong connection between being a writer - I feel as though I know what it feels like inside and I can say I've experienced similar problems and solutions from the inside. And I think that's a great advantage as a critic, because you know what the writer is feeling.

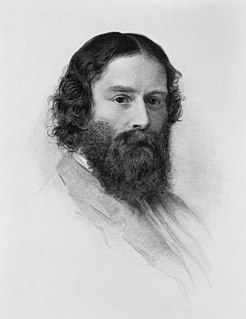

The library is not a shrine for the worship of books. It is not a temple where literary incense must be burned or where one's one devotion to the bound book is expressed in ritual. A library, to modify the famous metaphor of Socrates, should be the delivery room for the birth of ideas - a place where history comes to life.