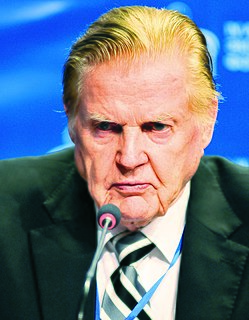

A Quote by Mehdi Hasan

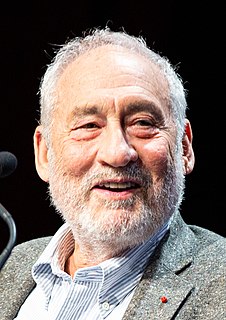

Let's start with the euro. What on earth were we thinking? How could anyone with the faintest grasp of economics have believed it was anything other than sheer insanity to yoke together diverse national economies such as Greece, Ireland, Germany and Finland under a single exchange rate and a single interest rate?

Related Quotes

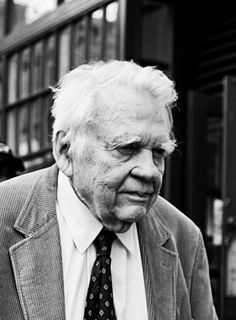

If a country is an attractive place for foreigners to invest their funds, then that country will have a relatively high exchange rate. If it's an unattractive place, it will have a relatively low exchange rate. Those are the fundamentals that determine the exchange rate in a floating exchange rate system.

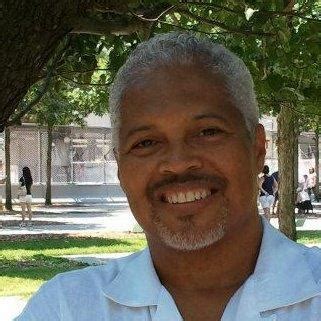

The lesson for Asia is; if you have a central bank, have a floating exchange rate; if you want to have a fixed exchange rate, abolish your central bank and adopt a currency board instead. Either extreme; a fixed exchange rate through a currency board, but no central bank, or a central bank plus truly floating exchange rates; either of those is a tenable arrangement. But a pegged exchange rate with a central bank is a recipe for trouble.

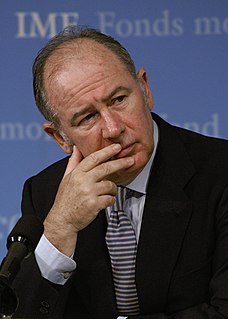

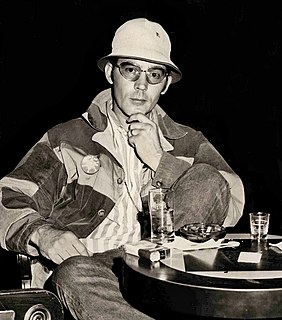

The IMF insisted that both Russia and Brazil maintain their currency at over-valued levels. Who are you protecting when you try to maintain that exchange rate by having high interest rates? You're protecting domestic and foreign firms that have gambled on the exchange rate. And who is paying the price? The small businesses that did not gamble [and no longer can afford loans], the workers who are going to be put out of jobs.