A Quote by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Every man, in proportion to his virtue, considers himself, with respect to the great community of mankind, as the steward and guardian of their interests in the property which he chances to possess. Every man, in proportion to his wisdom, sees the manner in which it is his duty to employ the resources which the consent of mankind has intrusted to his discretion.

Related Quotes

Every one should consider himself as intrusted not only with his own conduct, but with that of others; and as accountable, not only for the duties which he neglects, or the crimes that he commits, but for that negligence and irregularity which he may encourage or inculcate. Every man, in whatever station, has, or endeavours to have his followers, admirers, and imitators, and has therefore the influence of his example to watch with care.

By Liberty I understand the Power which every Man has over his own Actions, and his Right to enjoy the Fruits of his Labour, Art, and Industry, as far as by it he hurts not the Society, or any Members of it, by taking from any Member, or by hindering him from enjoying what he himself enjoys. The Fruits of a Man's honest Industry are the just Rewards of it, ascertained to him by natural and eternal Equity, as is his Title to use them in the Manner which he thinks fit: And thus, with the above Limitations, every Man is sole Lord and Arbitrer of his own private Actions and Property.

Where no man thinks himself under any obligation to submit to another, and, instead of co-operating in one great scheme, every one hastens through by-paths to private profit, no great change can suddenly be made; nor is superior knowledge of much effect, where every man resolves to use his own eyes and his own judgment, and every one applauds his own dexterity and diligence, in proportion as he becomes rich sooner than his neighbour.

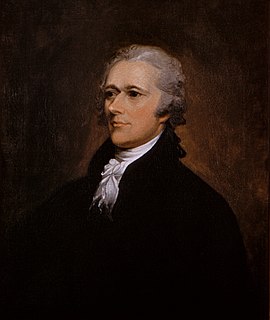

In the latter sense, a man has a property in his opinions and the free communication of them. He has a property of peculiar value in his religious opinions, and in the profession and practice dictated by them. He has an equal property in the free use of his faculties and free choice of the objects on which to employ them. In a word, as a man is said to have a right to his property, he may be equally said to have a property in his rights.

My conception of the audience is of a public each member of which is carrying about with him what he thinks is an anxiety, or a hope, or a preoccupation which is his alone and isolates him from mankind and in this respect at least the function of a play is to reveal him to himself so that he may touch others by virtue of the revelation of his mutuality with them. If only for this reason I regard the theater as a serious business, one that makes or should make man more human, which is to say, less alone.

The only distinction between freedom and slavery consists in this: In the former state a man is governed by the laws to which he has given his consent, either in person or by his representative; in the latter, he is governed by the will of another. In the one case, his life and property are his own; in the other, they depend upon the pleasure of his master. It is easy to discern which of these two states is preferable.

The man who has given himself to his country loves it better; the man who has fought for his friend honors him more; the man who has labored for his community values more highly the interests he has sought to conserve; the man who has wrought and planned and endured for the accomplishment of God's plan in the world sees the greatness of it, the divinity and glory of it, and is himself more perfectly assimilated to it.

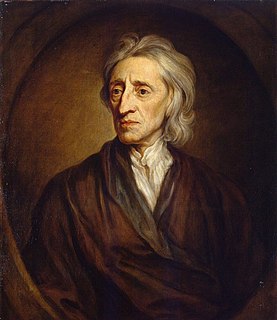

Thirdly, the supreme power cannot take from any man any part of his property without his own consent: for the preservation of property being the end of government, and that for which men enter into society, it necessarily supposes and requires, that the people should have property, without which they must be supposed to lose that, by entering into society, which was the end for which they entered into it; too gross an absurdity for any man to own.

Every man is of importance to himself, and, therefore, in his own opinion, to others; and, supposing the world already acquainted with his pleasures and his pains, is perhaps the first to publish injuries or misfortunes which had never been known unless related by himself, and at which those that hear them will only laugh, for no man sympathises with the sorrows of vanity.

In every system of theology, therefore, there is a chapter De libero arbitrio. This is a question which every theologian finds in his path, and which he must dispose of; and on the manner in which it is determined depends his theology, and of course his religion, so far as his theology is to him a truth and reality

Ownership by delegation is a contradiction in terms. When men say, for instance (by a false metaphor), that each member of the public should feel himself an owner of public property-such as a Town Park-and should therefore respect it as his own, they are saying something which all our experience proves to be completely false. No man feels of public property that it is his own; no man will treat it with the care of the affection of a thing which is his own.

It is not the right of property which is protected, but the right to property. Property, per se, has no rights; but the individual - the man - has three great rights, equally sacred from arbitrary interference: the right to his life, the right to his liberty, the right to his property The three rights are so bound together as to be essentially one right. To give a man his life but to deny him his liberty, is to take from him all that makes his life worth living. To give him his liberty but take from him the property which is the fruit and badge of his liberty is to still leave him a slave.

..every Man has a Property in his own Person. This no Body has any Right to but himself. The Labour of his Body, and the Work of his Hands, we may say, are properly his. .... The great and chief end therefore, of Mens uniting into Commonwealths, and putting themselves under Government, is the Preservation of their Property.

The American city should be a collection of communities where every member has a right to belong. It should be a place where every man feels safe on his streets and in the house of his friends. It should be a place where each individual's dignity and self-respect is strengthened by the respect and affection of his neighbors. It should be a place where each of us can find the satisfaction and warmth which comes from being a member of the community of man. This is what man sought at the dawn of civilization. It is what we seek today.