A Quote by Peter Molyneux

I've been in the industry doing games since the BBC Micro, the Acorn Atom, the Commodore 64.

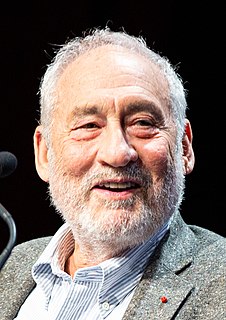

Related Quotes

I think what they've been doing is largely almost in firefighting mode without a good conceptual framework - either at the micro or the macro level. Micro, you would ask: "What kind of financial or banking system do we want?" Macro, you would say: "What are the underlying problems in the structure of our economy?"

We are, in a certain way, defined as much by our potential as by its expression. There is a great difference between an acorn and a little bit of wood carved into an acorn shape, a difference not always readily apparent to the naked eye. The difference is there even if the acorn never has the opportunity to plant itself and become an oak. Remembering its potential changes the way in which we think of the acorn and react to it. How we value it. If an acorn were conscious, knowing its potential would change the way that it might think and feel about itself.