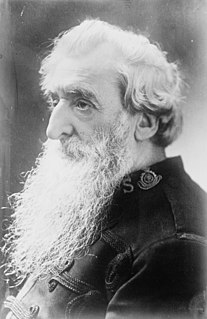

A Quote by Ralph Waldo Emerson

Nature arms each man with some faculty which enables him to do easily some feat impossible to any other, and thus makes him necessary to society. ... Society can never prosper, but must always be bankrupt, until every man does that which he was created to do.

Related Quotes

The crime which bankrupts men and states is job-work-declining from your main design, to serve a turn here and there. Nothing is beneath you, if it is in the direction of your life, nothing is great or desirable if it is off from that. I think we are entitled here to draw a straight line and say that society can never prosper but must always be bankrupts, until every man does that which he was created to do.

We must have kings, we must have nobles; nature is always providing such in every society; only let us have the real instead of the titular. In every society some are born to rule, and some to advise. The chief is the chief all the world over, only not his cap and plume. It is only this dislike of the pretender which makes men sometimes unjust to the true and finished man.

To refuse any bond of union between man and civil society, on the one hand, and God the Creator and consequently the supreme Law-giver, on the other, is plainly repugnant to the nature, not only of man, but of all created things; for, of necessity, all effects must in some proper way be connected with their cause; and it belongs to the perfection of every nature to contain itself within that sphere and grade which the order of nature has assigned to it, namely, that the lower should be subject and obedient to the higher.

To get a man soundly saved it is not enough to put on him a pair of new breeches, to give him regular work, or even to give him a University education. These things are all outside a man, and if the inside remains unchanged you have wasted your labor. You must in some way or other graft upon the man's nature a new nature, which has in it the element of the Divine.

Society is to the individual what the sun and showers are to the seed. It develops him, expands him, unfolds him, calls him out of himself. Other men are his opportunity. Each one is a match which ignites some new tinder in him unignitible by any previous match. Without these the sparks of individuality would sleep in him forever.

By Liberty I understand the Power which every Man has over his own Actions, and his Right to enjoy the Fruits of his Labour, Art, and Industry, as far as by it he hurts not the Society, or any Members of it, by taking from any Member, or by hindering him from enjoying what he himself enjoys. The Fruits of a Man's honest Industry are the just Rewards of it, ascertained to him by natural and eternal Equity, as is his Title to use them in the Manner which he thinks fit: And thus, with the above Limitations, every Man is sole Lord and Arbitrer of his own private Actions and Property.

There is a time in every man's education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better, for worse, as his portion; that though the wide universe is full of good, no kernel of nourishing corn can come to him but through his toil bestowed on that plot of ground which is given to him to till. The power which resides in him is new in nature, and none but he knows what that is which he can do, nor does he know until he has tried.

Society is an illusion to the young citizen. It lies before him in rigid repose, with certain names, men, and institutions, rootedlike oak-trees to the centre, round which all arrange themselves the best they can. But the old statesman knows that society is fluid; there are no such roots and centres; but any particle may suddenly become the centre of the movement, and compel the system to gyrate round it, as every man of strong will, like Pisistratus, or Cromwell, does for a time, and every man of truth, like Plato, or Paul, does forever.

Every man, however hopeless his pretensions may appear, has some project by which he hopes to rise to reputation; some art by which he imagines that the attention of the world will be attracted; some quality, good or bad, which discriminates him from the common herd of mortals, and by which others may be persuaded to love, or compelled to fear him.

What a man does, that he has. What has he to do with hope or fear? In himself is his might. Let him regard no good as solid but that which is in his nature, and which must grow out of him as long as he exists. The goods of fortune may come and go like summer leaves; let him scatter them on every wind as the momentary signs of his infinite productiveness.

Man cannot be exempted from his divinely-imposed obligations toward civil society, and the representatives of authority have the right to coerce him when he refuses without reason to do his duty. Society, on the other hand, cannot defraud man of his God-granted right... Nor can society systematically void these rights by making their use impossible.

My reason taught me that I could not have made one of my own qualities - they were forced upon me by Nature; that my language, religion, and habits were forced upon me by Society; and that I was entirely the child of Nature and Society; that Nature gave the qualities and Society directed them. Thus was I forced, through seeing the error of their foundation, to abandon all belief in every religion which had been taught by man.