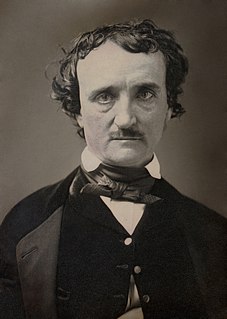

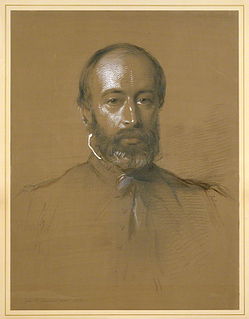

A Quote by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Milton had a highly imaginative, Cowley a very fanciful mind.

Related Quotes

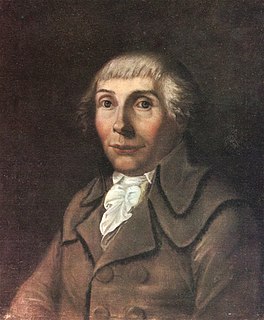

In the thirties a whole school of criticism bogged down intellectually in those agitprop, social-realistic days. A play had to be progressive. A number of plays by playwrights who were thought very highly of then - they were very bad playwrights - were highly praised because their themes were intellectually and politically proper. This intellectual morass is very dangerous, it seems to me. A form of censorship.