A Quote by Seth Shostak

Very few societies on Earth developed science as we know it today. On the other hand, the number is not zero - the Greeks, the Chinese, and the Maya did, among others. Once invented, science proved so useful that it spread like mold on a petri dish.

Related Quotes

Science only means knowledge; and for [Greek] ancients it did only mean knowledge. Thus the favorite science of the Greeks was Astronomy, because it was as abstract as Algebra. ... We may say that the great Greek ideal was to have no use for useful things. The Slave was he who learned useful things; the Freeman was he who learned useless things. This still remains the ideal of many noble men of science, in the sense they do desire truth as the great Greeks desired it; and their attitude is an external protest against vulgarity of utilitarianism.

But concerning vision alone is a separate science formed among philosophers, namely, optics, and not concerning any other sense ... It is possible that some other science may be more useful, but no other science has so much sweetness and beauty of utility. Therefore it is the flower of the whole of philosophy and through it, and not without it, can the other sciences be known.

Science and vision are not opposites or even at odds. They need each other. I sometimes hear other startup folks say something along the lines of: 'If entrepreneurship was a science, then anyone could do it.' I'd like to point out that even science is a science, and still very few people can do it, let alone do it well.

Science was blamed for all the horrors of World War I, just as it's blamed today for nuclear weapons and quite rightly. I mean World War I was a horrible war and it was mostly the fault of science, so that was in a way a very bad time for science, but on the other hand we were winning all these Nobel Prizes.

I wanted to be a scientist. My undergraduate degree is in biology, and I really did think I might go off and be some kind of a lady Darwin someplace. It turned out that I'm really awful at science and that I have no gift for actually doing science myself. But I'm very interested in others who practice science and in the stories of science.

I can think of very few science books I've read that I've called useful. What they've been is wonderful. They've actually made me feel that the world around me is a much fuller, much more wonderful, much more awesome place than I ever realized it was. That has been, for me, the wonder of science. That's why science fiction retains its compelling fascination for people. That's why the move of science fiction into biology is so intriguing. I think that science has got a wonderful story to tell.

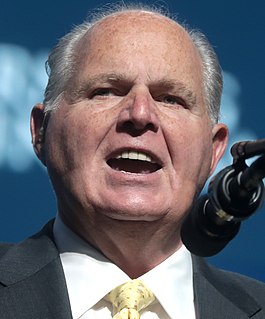

Science is science. Science is what is. After discovery, tests, trial, if a consensus of scientists today said that the sun orbits around the earth, would we say that they're right simply because there is a consensus? No. Because we know the earth orbits around the sun just as if there were a consensus that the earth is flat would we agree with them? No. So there can't be a consensus on something that hasn't been proven. This is a political movement. This whole global warming thing is a political movement.

The true contrast between science and religion is that science unites the world and makes it possible for people of widely differing backgrounds to work together and to cooperate. Religion, on the other hand, by its very claim to know “The Truth” through “revelation,” is inherently divisive and a creator of separatism and hostility.