A Quote by Thomas A. Steitz

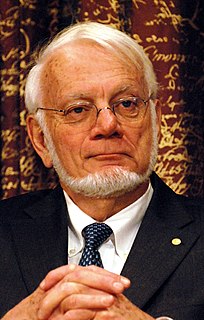

I began my thesis research at Harvard by working with a team in the laboratory of William N. Lipscomb, a Nobel chemistry Laureate, in 1976, on the structure of carboxypeptidase A. I did postdoctoral studies with David Blow at the MRC lab of Molecular Biology in Cambridge studying chymotrypsin.

Related Quotes

I grew up in Muenchen where my father has been a professor for pharmaceutic chemistry at the university. He had studied chemistry and medicine, having been a research student in Leipzig with Wilhelm Ostwald, the Nobel Laureate 1909. So I became familiar with the life of a scientist in a chemical laboratory quite early.

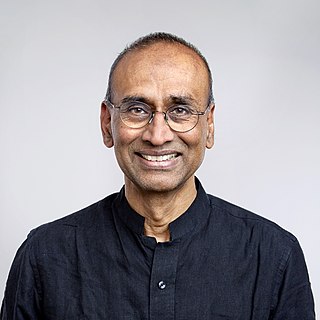

The students of biodiversity, the ones we most need in science today, have an enormous task ahead of molecular biology and the medical scientists. Studying model species is a great idea, but we need to combine that with biodiversity studies and have those properly supported because of the contribution they can make to conservation biology, to agrobiology, to the attainment of a sustainable world.

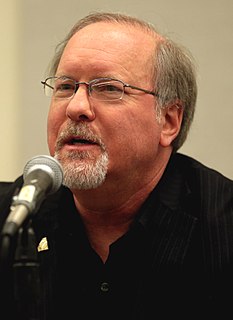

Part of the appeal was that Medawar was not only a Nobel Laureate, but he seemed like a Nobel Laureate; he was everything one thought a Nobel Laureate ought to be. If you have ever wondered why scientists like Popper, try Medawar's exposition. Actually most Popperian scientists have probably never tried reading anything but Medawar's exposition.

If belief in evolution is a requirement to be a real scientist, it’s interesting to consider a quote from Dr. Marc Kirschner, founding chair of the Department of Systems Biology at Harvard Medical School:

“In fact, over the last 100 years, almost all of biology has proceeded independent of evolution, except evolutionary biology itself. Molecular biology, biochemistry, physiology, have not taken evolution into account at all.

It is now widely realized that nearly all the 'classical' problems of molecular biology have either been solved or will be solved in the next decade. The entry of large numbers of American and other biochemists into the field will ensure that all the chemical details of replication and transcription will be elucidated. Because of this, I have long felt that the future of molecular biology lies in the extension of research to other fields of biology, notably development and the nervous system.