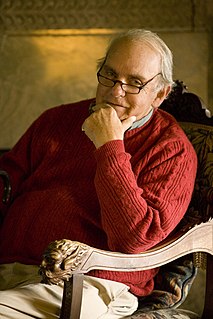

A Quote by A. S. Byatt

I know that part of the reason I read Tolkien when I'm ill is that there is an almost total absence of sexuality in his world, which is restful.

Related Quotes

But what will he do when he sees only too clearly why his patient is ill; when he sees that it arises from his having no love, but only sexuality; no faith, because he is afraid to grope in the dark; no hope, because he is disillusioned by the world and by life; and no understanding, because he has failed to read the meaning of his own existence?

Part of the inner world of everyone is this sense of emptiness, unease, incompleteness, and I believe that this in itself is a word from God, that this is the sound that God’s voice makes in a world that has explained him away. In such a world, I suspect that maybe God speaks to us most clearly through his silence, his absence, so that we know him best through our missing him.

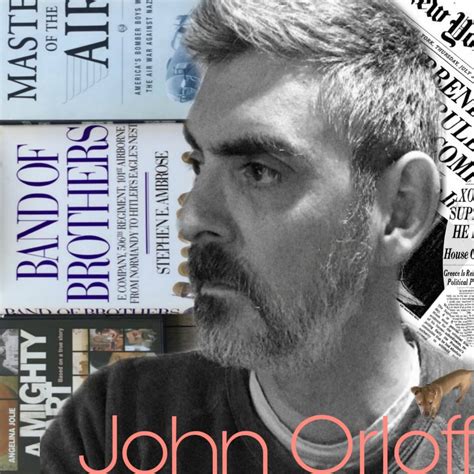

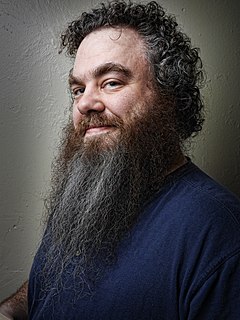

I think the tendency to over-explain and over describe is one of the most common failings in fantasy. It's an unfortunate piece of Tolkien's legacy. Don't get me wrong, Tolkien was a great worldbuilder, but he got a little caught up describing his world at times, at the expense of the overall story.

To read" actually comes from the Latin reri "to calculate, to think" which is not only the progenitor of "read" but of "reason" as well, both of which hail from the Greek arariskein "to fit." Aside from giving us "reason," arariskein also gives us an unlikely sibling, Latin arma meaning "weapons." It seems that "to fit" the world or to make sense of it requires either reason or arms.

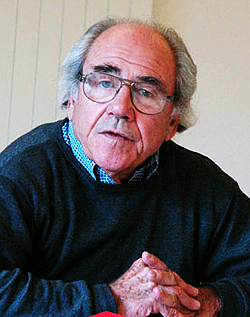

When Peter Jackson did The Lord of the Rings trilogy with Fellowship of the Ring, not everyone had read Tolkien, and yet somehow with that scope and the spectacle of that fantasy, people were willing to give it a shot. And when they watched the first one, the characters drew them in and they started understanding the story. And then, all of a sudden, they were The Lord of the Rings fans, even if they never read Tolkien.

It is alone that part of the external universe which we call material which acts on man through his senses - that part of which we ordinarily feel our knowledge to be the surest; but in reality, strangely enough, as will soon appear, this is one of the aspects of the external world, of which we can know nothing.