A Quote by Aage Bohr

I have been connected with the Niels Bohr Institute since the completion of my university studies, first as a research fellow and, from 1956, as a professor of physics at the University of Copenhagen. After the death of my father in 1962, I followed him as director of the Institute until 1970.

Related Quotes

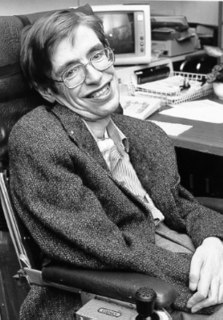

This is the most important joke I've ever heard. Niels Bohr, the founder of Quantum Physics, had a friend to dinner. As the friend left, he noticed a horseshoe nailed above Bohr's front door. He said to Bohr, accusingly, "Niels, you're a great scientist. You can't believe in superstitions." Bohr answered, "I don't, but apparently it works anyway."As with confirmation bias, we tend to lean toward superstitions that benefit us.

In 1946, Oxford University in England was offered large funds to create a new Institute of Human Nutrition. The University refused the funds on the ground that the knowledge of human nutrition was essentially complete, and that the proposed institution would soon run out of meaningful research projects.

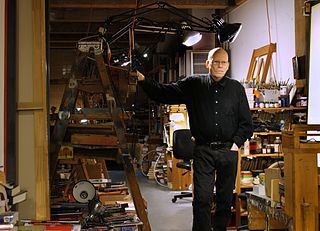

The Babson Institute, which is now an actual university, was started by this guy [my father] who also had a problem with believing in gravity. And so he started the Babson Institute in New Boston, New Hampshire, which then moved to Gloucester. Each year they have a competition of one thousand dollars for one thousand words of an essay on gravity. That's the way they do it.

The director of the institute where I was working apologized about these young, enthusiastic researchers when the World Bank visited because he was afraid the institute would lose the World Bank consultancies.I went back home and started the Research Foundation for Science, Technology, and Ecology?an extremely elaborate name for the tiny institute that I started in my mother?s cow shed. My parents handed over family resources and said, ?Put them to public purpose.? That?s how I survived.

In 1986, I was asked by the then-Dean of Science at the University of British Columbia, Dr. R.C. Miller, Jr., to establish a new interdisciplinary institute, the Biotechnology Laboratory. I decided that it was time for me to start paying back for the thirty years of fun that I had been able to have in research.

I became a member of the faculty at Northwestern University in 1965 but did not complete my thesis until two years later at a graduate ceremony at which Carnegie Institute of Technology became Carnegie-Mellon University. At Northwestern, I was mentored by the 'three Bobs:' Robert Eisner, Robert Strotz and Robert Clower.